By Michael Brooke

The population of Canada is getting older. You’ve probably heard that the fastest-growing demographic is those folks over 100. But demographics are only part of the story. As a reader of DM Magazine, you base most of your critical decisions on data. But sometimes, marketers ignore what is staring at them right in the face in the quest for more sales.

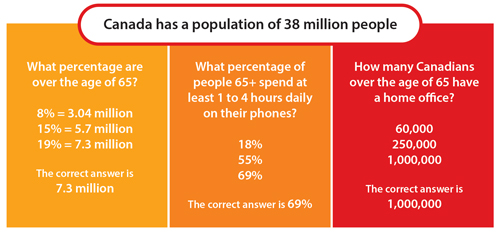

Here are three simple questions that are data-driven concerning demographics.

In a new book entitled SuperAgeing, former advertising executives David Cravit and Larry Wolf strongly believe that marketers need a whole new way of looking at what it means to be 65 and up.

As they explain it, the old way (literally) is something called DefaultAging. It still dominates healthcare, economics, housing, business, and virtually every aspect of our society. It views “old” as a condition that kicks in, almost abruptly, when you reach the traditional retirement age of 65.

David Cravit

Larry Wolf

“Old” means: You haven’t much time left (maybe 10–15 years).

You have worsening physical and mental health, so you can’t do much, and society shouldn’t expect much.

The best you can do is to minimize your suffering to achieve a relatively pain-free and dignified glide path to the finish line, which isn’t far away.

There are no positives, nothing else that “getting older” can bring you once you hit “old.”

For Cravit and Wolf, demographics is not just destiny; it is multi-dimensional. They argue for a new way to view ageing: not just mathematically more years, but different years, with dramatically different characteristics.

Instead of a relatively short, painful period of decline, ageing becomes a dynamic, favourable time. Instead of mere survival, there is growth, development, new possibilities, and achievements.

What’s new and different — revolutionary, in fact — is how those “ageing years” are spent. And that comes from a whole new way of looking at what ageing is in the first place, along with a radical new way of managing it: SuperAging.

I had an opportunity to sit down with both authors on a bright sunny day in May. Our conversation started with a particularly contentious issue: ageism when marketing products and services. “Several folks are stuck on the obsolete model. This model is that at 65, you might have twelve years left, and you probably don’t have much time to do anything,” explains David.

But things are radically changing. Many in the 65+ demographic are not in a defensive role regarding retirement. Instead, SuperAgers recognize they have 25 to 30 years left and intend to make the most of those years.

While many marketers focus on the holy grail of the 18-34 demographic, the numbers of what is happening in the real world can sometimes tell a very different story.

Take vehicle purchases, for example. Bob Hoffman wrote on his Ad Contrarian website, “The auto industry continues to target 18-34-year-olds who account for only 12 percent of subcompact car sales. Meanwhile, they essentially ignore the 88 percent of the population who buy these “youth” cars. “How many car commercials do you see where there are drivers over the age of 55? The answer is zero,” exclaims David.

“When you look at the ages of those who work in advertising and marketing, many of those people are in their late twenties and thirties,” says Larry. “Middle managers tend to be in their 40’s. Very senior management could be in their 50’s, and that’s about where things top out.” As Larry points out, finding a marketing manager over 60 is rare.

The phenomenon of active longevity is something new for many in society, including those who work in the marketing world. Several factors have propelled a longer life for those 65 and up. This includes medical breakthroughs, the promotion of a more balanced and healthier diet and the popularity of exercising.

David believes many marketers are infatuated with clicks and technology but must remember what it takes to drive sales. “How does a company like Vice, which was once valued at 6 billion dollars, get sold off for less than 250 million?” he asks. “Ultimately, what it boils down to is the question every consumer (including those over 65) will ask: ‘What is it that you’re providing that I need?’”

SuperAgeing explains with great clarity that the Baby Boomers are collectively ageing in many different ways. The boomer marketplace has its unique segments. “The mistake is to assume that age is everything,” explains David. “The behaviour of those born between 1946 and 1964 differs greatly from the previous generation. The problem is that media is bought by age. For a group that worships data, why don’t they see the reality of the behaviour?” But maybe the answer lies with Oscar Wilde, who famously said, “The old believe everything; the middle-aged suspect everything; the young know everything.”