Companies often overestimate the loyalty of their customers, mistakenly believing that repurchase behaviour is an indicator of how they feel about the brand. But true loyalty is born out of a deeply held conviction that the brand cares as much about them as they do about the brand.

By Stephen Shaw

By Stephen Shaw

If you had lived in the mid-to-late nineteenth century in America the chances are you would have known the name Benjamin Talbot Babbitt.

Babbitt was a New York business owner whose company was the first to manufacture and market soap in individual bars. “Babbitt’s Best Soap” could be found in most homes at the time, attributable to his pioneering use of national advertising to promote his brand. The product’s ad slogan: “Full of hope with Babbitt’s soap”.

Babbitt was a self-made man and inventor, born on a farm, who made his fortune making soap and other products like baking soda. But while he made his reputation as a soap maker, he also deserves credit as the first merchant to create what we now call a loyalty program.

Babbitt’s clever idea was to encourage buyers to collect and mail in the trade marks from his soap packages in return for free lithographic prints. Later he expanded the range of redeemable gifts and listed them in a catalogue called “The Mailing List of Premiums”.1

Ever since then this “Give and Get” model has pretty much remained the same for most modern-day loyalty programs: In exchange for buying stuff, customers are issued a tokenized currency which they can redeem for free goods. More often than not, that currency takes the form of points.

Since that emergent era in the 1850s loyalty programs have grown pervasive. For many companies they form the cornerstone of their CX strategy. It’s estimated that 90% of consumer companies in North America operate a frequency marketing program of some kind. Airlines, restaurants, hotels, grocers, coffee shops, banks, apparel makers, gas retailers – in fact, retailers of all kinds – you name it, there’s a membership program you can sign up for.

Since that emergent era in the 1850s loyalty programs have grown pervasive. For many companies they form the cornerstone of their CX strategy. It’s estimated that 90% of consumer companies in North America operate a frequency marketing program of some kind. Airlines, restaurants, hotels, grocers, coffee shops, banks, apparel makers, gas retailers – in fact, retailers of all kinds – you name it, there’s a membership program you can sign up for.

Billions of loyalty points are issued every year. Worldwide the loyalty market stands at $14 billion and is expected to grow at a compound annual rate of 17% over the next decade, reaching $61 billion2. In Canada the market is growing almost as fast. According to one estimate it’s valued at almost $2 billion, up 15% over last year, while projected growth is 12%.3 The average Canadian reportedly belongs to as many as 19 programs (but is active only in 7).4

The question, of course, is whether all of that expense, all of that effort, all of those billions of points, pays off in more loyal customers who will buy more, more often, for longer than they might otherwise. There is enough evidence to conclude that customers will indeed spend more; that these programs do generate incremental revenue; and that they in fact serve as an effective barrier to exit. But are companies paying extra for purchases that would have occurred anyway? Are they just a more targeted form of household flyer? Do they make customers appreciably more loyal? Or is all just a parlour game where companies reward people with their own money? An illusion of loyalty more than actuality.

The Frequency Model

If Milwaukee department store owner Ed Schuster were still alive today, he would wholeheartedly endorse the claim that loyalty programs do pay off. In 1891 he came up with a unique program for his store that used stamps as the loyalty currency. Customers got one stamp for every ten cents they spent which they could paste into a collector book and redeem for rewards once they had enough saved up. It was hugely popular with his customers.

Seeing the success of trading stamps at Schuster’s, a New Jersey silverware salesman by the name of Thomas Sperry figured a lot of other retailers might also be interested in adopting a similar program if a third party vendor would take over the trouble and expense of running it for them. In 1896 he teamed up with Michigan businessman Shelley Hutchinson to form the Sperry and Hutchinson Company and began selling “S&H Green Stamps” to retailers who would then hand them out to their customers. Shoppers would then exchange their saved stamps at S&H-owned redemption centers for products listed in an “IdeaBook” catalog.

Seeing the success of trading stamps at Schuster’s, a New Jersey silverware salesman by the name of Thomas Sperry figured a lot of other retailers might also be interested in adopting a similar program if a third party vendor would take over the trouble and expense of running it for them. In 1896 he teamed up with Michigan businessman Shelley Hutchinson to form the Sperry and Hutchinson Company and began selling “S&H Green Stamps” to retailers who would then hand them out to their customers. Shoppers would then exchange their saved stamps at S&H-owned redemption centers for products listed in an “IdeaBook” catalog.

Trading stamps remained a common feature of retail merchandising through the first half of the 20th century but only became widely used in the early 1950s when supermarkets began issuing them. Within a five year period the trading stamp business quintupled in size, reaching peak popularity in the 1960s when 80% of American households were collecting stamps. But then as the economy slumped in the 1970s struggling grocers gave up trading stamps in favour of an everyday low price model, saving themselves the program expense. Stamp-based loyalty programs lost their promotional appeal and eventually faded away.

The first retailer to issue its own proprietary currency was Canadian Tire in 1958 as a way to boost traffic at its gas bars. Instead of lowering prices to compete head on with the major oil companies, Canadian Tire issued rebate coupons printed on banknote paper, giving it the feel of real money, which made them seem more valuable and worth holding on to. The coupons became so popular with Canadians that at one point they were deemed Canada’s second official currency and remained in circulation until they were slowly phased out, supplanted by the Triangle Rewards Card program.

Fast forward to 1981 when American Airlines launched its AAdvantage frequent flyer program offering free flights and upgrades based on the number of miles flown. At the time airline deregulation had spawned many new regional and discount carriers offering low fares, making air travel more affordable for the average person. Unwilling to engage in a race-to-the-bottom fare war with this insurgent flock of carriers, American Airlines scanned its SABRE reservation system for its most frequent flyers and in an effort to insulate them from competitive poaching sent them an invitation to join the program. The response was so overwhelming that it triggered a wave of copycat programs amongst the other airlines, including Air Canada’s Aeroplan in 1984. Seeing the airline programs take off amongst the highly coveted “road warriors”, hotels were quick to adopt the frequency model, beginning with Holiday Inn’s Priority Club in 1983. Car rental agencies followed soon after and then, as retail POS systems began to modernize, retailers started card-based programs of their own, beginning with Neiman Marcus in 1984 and Nordstrom in 1987.

Fast forward to 1981 when American Airlines launched its AAdvantage frequent flyer program offering free flights and upgrades based on the number of miles flown. At the time airline deregulation had spawned many new regional and discount carriers offering low fares, making air travel more affordable for the average person. Unwilling to engage in a race-to-the-bottom fare war with this insurgent flock of carriers, American Airlines scanned its SABRE reservation system for its most frequent flyers and in an effort to insulate them from competitive poaching sent them an invitation to join the program. The response was so overwhelming that it triggered a wave of copycat programs amongst the other airlines, including Air Canada’s Aeroplan in 1984. Seeing the airline programs take off amongst the highly coveted “road warriors”, hotels were quick to adopt the frequency model, beginning with Holiday Inn’s Priority Club in 1983. Car rental agencies followed soon after and then, as retail POS systems began to modernize, retailers started card-based programs of their own, beginning with Neiman Marcus in 1984 and Nordstrom in 1987.

“The U.K. supermarket chain Tesco that blazed a trail for the grocery business in the use of customer data with the launch of its ClubCard program in 1995”

The first grocer to offer a loyalty program was Safeway in 1990. But it was the U.K. supermarket chain Tesco that blazed a trail for the grocery business in the use of customer data with the launch of its ClubCard program in 1995. ClubCard members were given exclusive access to the lowest prices which enticed 90% of shoppers to sign up for the program. With the help of data mining firm Dunnhumby, Tesco pioneered the use of customer-level purchase data to individualize discounts and rewards. Within a year of its launch ClubCard members were spending close to one third more at Tesco than rival Sainsbury, proving to the retail industry that a data-driven loyalty program could help to consolidate shopper spending.

Here in Canada the Shoppers Drug Mart pharmacy, inspired in part by the success of Tesco’s ClubCard, adopted a similar model in designing its Optimum program. Launched in 2000 with the full weight of the company behind it, the program hit its first-year enrollment target of four million members within the first three months. After grocery giant Loblaw acquired Shoppers Drug Mart the company merged Optimum with its own PC Plus program in 2018 to form the largest consumer database in the country. Now shoppers could earn and redeem points across the entire network of Loblaw grocery banners and Shopper’s Drug Mart stores.

Today PC Optimum is Canada’s most popular loyalty program with 17 million members. Shoppers are sent weekly individualized offers which they download to their phone. Savvy members can maximize points earnings by taking advantage of select in-store product bonuses and threshold events (“Get 20x the points when you spend $XX or more”). The bank of points can then be converted into major food savings. Meanwhile Loblaw gains a microscopic view of shopping behaviour, enabling it to drive sales of higher margin products, increase basket size and encourage cross-category shopping. Most large grocers now run comparable programs, recognizing the value of the customer-level data.

For companies unwilling to go to the trouble of operating their own proprietary loyalty club, the option in Canada has always been to join the Air Miles Coalition program, launched in 1992, and now owned and operated by founding partner Bank of Montreal. In its halcyon days Air Miles had two-thirds of Canadian households signed up and a blue chip roster of national and regional sponsors in all of the high frequency categories – gas, groceries, liquor, credit card, and retail.

In the mid-2000s a succession of corporate missteps shredded Air Miles’ reputation. The company devalued Miles; slapped a 5-year expiry date on earned Miles (a shortsighted decision that was quickly reversed after a public outcry, triggering stricter regulatory scrutiny); and then reclassified Mileage rewards into “cash” and “travel” types which only served to confuse members. On top of all that, the customer service call centre was notorious for long wait times as members sought to claim missing points (which happened often) or book air travel (which became harder due to seat restrictions). Eventually a downward spiral in membership led to a major exodus of unhappy sponsors, culminating in a bankruptcy filing in 2023 and the subsequent rescue by BMO.

The Loyalty Game

Today it’s never been easier for companies of all types and sizes to set up and run a frequency marketing program. If a company is worried about the points liability risk it just needs to take its cue from Starbucks which generates half its revenue from members of its reward program, or Sephora’s Beauty Insider program whose 17 million members account for 80% of its sales. In the case of both those companies, the loyalty program serves as a gateway to a broader, deeper, more lucrative member relationship.

Every sector has its own success stories to draw inspiration from. Take hotels for instance which have been playing the loyalty game for almost as long as the airlines. They’ve had time to sand off all the rough edges. And none of them would ever dare to give up those programs for fear of driving away their highest margin guests. Frequent stay programs have become an indispensable part of the overall guest experience.

“Attract enough members to your loyalty program and you can control your destiny as a business”

In 2024 hotel loyalty members accounted for 53% of occupied rooms and have proven to be a surefire way for hotel operators to smooth out room demand even in low seasons5. The more sophisticated programs mix financial rewards with experiential benefits. For example, in the case of Marriott’s Bonvoy program, members can use their points to gain exclusive VIP access to major sporting events, concerts, and culinary classes, creating truly indelible guest memories. The emphasis in the more advanced programs shifted from “free” to “value added”, making guests feel they’re getting more than a fair return on their points.

Unlike the past when licensed on-site loyalty platforms were often priced out of reach for most companies, there are many cloud-based, mobile-enabled solutions available today that make it relatively simple to automate account sign-ups, synchronize customer data across systems, update accounts in real-time, allow cross-channel point collection, enable targeted offers, and allow for instant reward redemption. And to help figure out the optimal reward design and program logistics, companies can call on an entire ecosystem of consultants, data analysts, systems integrators and service providers who have honed their expertise over the past quarter century.

The business case for a loyalty program practically writes itself. Attract enough members to your loyalty program and you can control your destiny as a business. You can restrict discounts to just those customers deserving of them. You can incentivize people to buy more of what you have to sell. You can reward your best customers with bonus savings and special entitlements. You can shrink the interval time between online or offline visits with timely phone notifications and email reminders. You can monitor buying behaviour in real time so that you can react faster to sales trends. You can identify and reactivate dormant customers.

So what’s not to like?

False Sense of Security

For starters, you’ve conditioned customers to become shopping mercenaries, on the constant look-out for the best deal, the sweetest rewards, the richest bonus offers. For a lot of members collecting points can become an addiction. They turn into points junkies. It gives them a dopamine kick. They love to play the game. And there are plenty of third party resources to show them how to take maximum advantage of their points. Which is why members are often more loyal to the program than the brand.

An avid collector will go out of their way to fill their piggy bank with points – to chase after the next highest reward tier – to avoid, at all cost, paying full price for anything. Especially if they are “frenemies” of the brand. They may not love the brand but the program rewards are generous enough to keep them tethered to it. It is a paper thin transactional relationship, with only the size of the unredeemed points balance standing in the way of a customer shopping elsewhere.

Just consider Loblaw’s PC Optimum program. According to NPS tracker Comparably, Loblaw’s Net Promoter Score is a negative 8%, the worst of all the national grocers in Canada. The number of Detractors is over 40%. One shopper who is in the top one percent of PC Optimum points earners says: “My only incentive [to being a member] is to avoid being ripped off”. And she is not alone. Members feel they are being duped. They are constantly fuming on Reddit about their experience. They feel pressured to buy products they don’t need – complain about indifferent customer support – and mostly feel that store prices are marked up excessively to pay for points. One shopper posts, “I’m sure the points redeemed is a fraction of the profits they make by overcharging products”; another complains, “Basically, Optimum was designed from the get-go to reward you with your own money”. A particular sore point is this common refrain: “Numerous times I had to complain about missing points from promotions.”

“Loyalty Program Metrics Often Mask the Underlying Cracks in the Relationship”

The other major downside of points-based programs is that it leads companies to overestimate the loyalty of their customers. They are lulled into a false sense of security. All they can see is this growing member base – people who appear to be engaged – who are clicking on the bonus offers – who keep piling up points. But deep down those members really only care about one thing: saving money. That’s why they signed up. They are not as loyal as their “earn and burn” history might suggest.

After reporting that Loblaw redeemed more than a billion dollars worth of Optimum points in 2024, its CFO smugly noted, “What it reflects is that more and more consumers are liking PC Optimum”. Clearly, he doesn’t keep track of his company’s NPS score. A lot of his customers actually loath the company – accuse it of profiteering – bristle at what they believe to be deceptive merchandising – but, yes, they do like the program.

Loyalty program metrics often mask the underlying cracks in the relationship. Focused largely on short-term measures of success like point balances and redemptions, operators fail to see the revenue leakage that can occur over time as customers “quit quietly”, reducing their purchases, unhappy with their experience for one reason or another. The bitter complaints on social media are shrugged off as coming from chronic malcontents, even though the common sentiment amongst them is that the company cares more about its bottom line than their well being. And the truth is, few companies actually do care about their customers. Maybe less than ten percent, according to renowned loyalty expert Fred Reichheld.

All of which explains why people have become so cynical about the construct of loyalty programs: it’s a game they’re being forced to play, one stacked in favour of the operator. “Whether it actually benefits the consumer is irrelevant!”, grouses one PC Optimum member.

Survival Mode

The fact is people can no longer afford to be loyal. According to one news report, “Bank of Canada data show Canadian consumers feeling persistently negative about pretty much everything”.6 They fret about the rising cost of living. About falling further behind. About paying more to get less. Even middle income families are feeling the squeeze. They feel broke. And everywhere they shop they experience maddeningly poor customer service. The first thing they usually hear on dialing the call centre: “We are experiencing heavier than normal call volumes”, followed by a hold time that seems to stretch into infinity. When they finally get through, they are treated curtly by agents under orders to keep calls short. Or due to offshoring of call centres the agents speak heavily accented English making it hard to understand them. Calls are inexplicably dropped and customers have to start all over again. Callbacks never happen. No one has the full knowledge or authority to solve a problem, so calls get transferred from one person to another. Is it any wonder that people no longer feel valued or cared for? They certainly do not feel their needs are being put first. No surprise then that most people will switch brands in an instant for a better deal. Brand recognition no longer counts for much in the shopping aisle. People may be signing up for points programs in droves, but only because they are in survival mode: membership is a way for them to avoid being “ripped off”. And if they have to give up some of their privacy for the savings, that’s a trade-off most people can live with if it helps to make ends meet.

According to one study last year, 74% of Canadians report being less loyal than they were two years ago.7 And that finding is consistent with Forrester’s annual NPS rankings for the US and Canada: Down again last year, across all industries. In Canada the only sector that showed any improvement was the luxury automotive industry. According to Forester thirty six per cent of all brands saw significant decreases in their scores. All this despite the orgy of spending on loyalty programs.

The same disheartening story plays out in general customer satisfaction ratings. According to the latest American Customer Satisfaction Index, overall satisfaction has declined for three consecutive quarters now. It’s roughly at the level it was twelve years ago. This stagnation is due to a mismatch between people’s expectations and their lived reality. And satisfaction is a prerequisite to loyalty. They are two sides of the same coin. All of the points in the world can’t make up for a consistently poor customer experience. And according to ACSI the main reason for the dismal satisfaction ratings is that many businesses are extracting more from their customers while delivering less.

Malleable Middle

So in these trying economic times, when people are fed up with corporate doublespeak, with sanctimonious but hollow purpose statements from profit-first companies (like Loblaw’s vow of “Helping Canadians Live Life Well”), what does loyalty even mean?

The trouble is there is no single, universally accepted definition of loyalty, not even in the academic world. Does loyalty simply mean a willingness to buy a brand 100% of the time? Most of the time? What if people have no viable options? What if they stick with the brand only because it’s too much trouble to switch? Or the other choices are all the same? Maybe they’re just in a holding pattern until a better deal comes along. Or perhaps for convenience sake they just opt for the top-of-mind brand – or the one closest on the shelf – or the one “on special” that day. Or they simply don’t care enough about the category to really give their choice much thought at all. Moreover, loyalty differs by category – hotel loyalty is not the same as loyalty to your Apple watch or loyalty to the make of vehicle you drive or loyalty to the airline you fly and certainly not the same as loyalty to wherever you buy your groceries.

“The Trouble is There is no Single, Universally-Accepted Definition of Loyalty”

So if marketers can’t agree on a universal definition of loyalty, how can they know for sure whether customers are truly loyal?

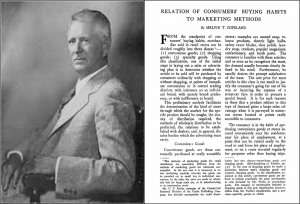

It turns out that the best and most enduring definition of loyalty was the very first one that surfaced in 1923 during the formative years of marketing. The legendary Harvard School Professor Melvin T. Copeland published a paper called “The Relation of Consumers’ Buying Habits to Marketing Methods” in which he offered this take on loyalty: “Consumers show such strong preferences for certain articles that they will make a special effort to secure them and will not accept substitutes.”8 Copeland observed that the intensity of loyalty varied according to the type of product being purchased – say, buying a box of cereal versus a new car versus an appliance. It all depended on how involved the customer was in the category – how large a role it played in their lives – their immediate past experience – and the amount of time available to consider the available options and trade-offs.

It turns out that the best and most enduring definition of loyalty was the very first one that surfaced in 1923 during the formative years of marketing. The legendary Harvard School Professor Melvin T. Copeland published a paper called “The Relation of Consumers’ Buying Habits to Marketing Methods” in which he offered this take on loyalty: “Consumers show such strong preferences for certain articles that they will make a special effort to secure them and will not accept substitutes.”8 Copeland observed that the intensity of loyalty varied according to the type of product being purchased – say, buying a box of cereal versus a new car versus an appliance. It all depended on how involved the customer was in the category – how large a role it played in their lives – their immediate past experience – and the amount of time available to consider the available options and trade-offs.

A distinction needs to be made between brand and customer loyalty. Brand loyalty is formed out of an emotional bond – a very strong feeling of preference and trust – where people relate to the brand – feel good about using it – identify with it. Whereas customer loyalty is a more rational choice based on differentiation and experience. Customers form favorable or unfavorable impressions over time based on the quality and distinctiveness of their experiences. A person can be loyal to a brand but not necessarily to the company that makes it – or loyal to a particular company but not to every brand it sells. True loyalty is in fact a hybrid emotion: “I would miss the brand if it went away” – “I find it really easy to do business with them”.

Most people have a small repertoire of brands they adore. Brands they turn to reflexively. And it can be for different reasons. They might feel, “I love this brand – it’s part of who I am”. Or “I love this brand – it never lets me down”. Or “I love this brand – it makes me feel happy”. Or “I love this brand – it shares my world view”. Or “I love this brand – it supports causes I believe in”.

The common denominator is how those brands make people feel. The oversized role those brands have in their lives. The brands they can’t live without. The brands they go out of their way to buy. The brands that are tattoo-worthy. They identify with them – they rave about them – they feel proud to use them. Those are the true brand loyalists – the advocates – the customers most committed to you – who will accept no substitutes.

The next level of loyalty are weathervane customers who value what you sell – believe you offer a better solution – prefer you for the time being to any of the other options. However, they would never go out of their way to buy from you. They are okay settling for the next best brand if they must. “Better”, from their perspective, is a moving target.

Then there are the passive customers who feel you are good enough – or maybe they just think all of your competitors are no better anyway, so why go through the bother of taking a chance on them? Especially if the category is a sea of sameness. Lowest price wins.

And then you have the bottom tier – both the opportunistic bargain-hunters, mercenary by nature, and the embittered “haters”, also known as “demon” customers, like the ones you might find on a sub-reddit with their pitchforks raised in anger, raging about corporate malfeasance and the latest brand provocation.

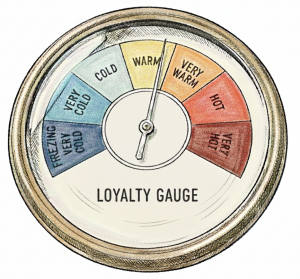

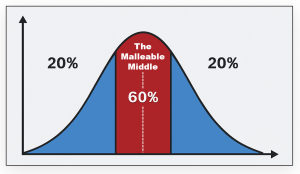

Loyalty is not a binary variable – yes or no – it is a continuous variable that can be measured on a linear scale, from “committed” to “enthused” to “ambivalent” to “tepid” to “fragile”. Or think of a temperature gauge: “Very Hot”, “Warm”; “Cold”; “Freezing”. If you drew a diagram the customer base would look like a Bell Curve, with 60% of customers in the “Malleable Middle”, capable of leaning one way or the other depending on whether they’re feeling “hot” or “cold”. The hardest part for marketers is to find out exactly how many customers are the most “malleable”, and then give them a reason to care. But before they can do that, marketers need a method to gauge the temperature. Who is hot? Who is warm? Who is cold?

Loyalty is not a binary variable – yes or no – it is a continuous variable that can be measured on a linear scale, from “committed” to “enthused” to “ambivalent” to “tepid” to “fragile”. Or think of a temperature gauge: “Very Hot”, “Warm”; “Cold”; “Freezing”. If you drew a diagram the customer base would look like a Bell Curve, with 60% of customers in the “Malleable Middle”, capable of leaning one way or the other depending on whether they’re feeling “hot” or “cold”. The hardest part for marketers is to find out exactly how many customers are the most “malleable”, and then give them a reason to care. But before they can do that, marketers need a method to gauge the temperature. Who is hot? Who is warm? Who is cold?

Commitment Score

Two thirds of Fortune 500 enterprises rely on Fred Reichheld’s Net Promoter Score as a beacon loyalty metric which often appears on their corporate scorecard. NPS is especially useful as a standardized benchmark tool to compare loyalty performance against competitors. And ever since it was first introduced in 2003, it has certainly raised the level of awareness in the corporate suite of the importance of loyalty. However, there’s been a backlash against NPS as a sole indicator of customer loyalty, as the Wall Street Journal pointed out, calling it a management fad that has to be used in combination with other measures if companies are going to have a true picture of where they stand with customers.9

The other major objection to NPS is that it doesn’t actually measure loyalty: customers don’t have to be loyal to a brand to recommend it. For many companies NPS actually serves more as a measure of satisfaction, used to track the quality of customer service in the aftermath of a recent interaction.

To understand the true state of the customer relationship, we need a more inclusive measurement equation that brings together emotional and behavioral metrics. That’s because loyalty lies at the intersection of three dimensions: Emotional – the level of brand trust and preference; Cognitive – whether customers believe the brand is functionally superior and offers a better experience; and Behavioral – which is how much and how often they re-purchase the brand. True loyalists are customers who rank highest across all three dimensions.

“The Most Committed Customers Are The True Brand Loyalists”

In Fred Reichheld’s 1993 classic book “The Loyalty Effect” in which he made a persuasive economic case for loyalty that still holds up today, you’ll find his famous claim that a 5% percent increase in retention translates into a 75% increase in lifetime profits. The “Loyalty Effect” is the increase in business growth and profitability over time as a result of creating more loyal customers. Customers should be treated as annuities whose lifetime value or “customer equity” increases with the right level of investment. You earn equity, not through giveaways and rewards, but by offering greater value than customers can get elsewhere – by delivering a superior and differentiated experience – and by winning the affection and devotion of customers.

In Fred Reichheld’s 1993 classic book “The Loyalty Effect” in which he made a persuasive economic case for loyalty that still holds up today, you’ll find his famous claim that a 5% percent increase in retention translates into a 75% increase in lifetime profits. The “Loyalty Effect” is the increase in business growth and profitability over time as a result of creating more loyal customers. Customers should be treated as annuities whose lifetime value or “customer equity” increases with the right level of investment. You earn equity, not through giveaways and rewards, but by offering greater value than customers can get elsewhere – by delivering a superior and differentiated experience – and by winning the affection and devotion of customers.

A holistic measurement system must therefore track both the “hard” behavioural metrics – year-over-year gains in incremental sales plus retained recurring revenue resulting from lower attrition – as well as the “soft” attitudinal measures that serve as leading indicators of purchase intent and repeat purchase. Those would include such measures as brand preference, advocacy, and level of commitment. Also important to track are customer portfolio measures like growth rate and velocity, average spending, cross-sell ratio, dormancy and attrition rates, levels of engagement, value migration, and much more.

The center console on the measurement dashboard has to be a Relationship Scorecard that can show the linkage between brand and customer health indices and the KPIs that corporate management obsesses over: market share, share of expenditures, and revenue growth. Prove that connection to the CFO and the money vault will swing wide open to fund continued investment in loyalty marketing.

To accurately gauge the emotional loyalty of customers you need to do qualitative and quantitative research – qualitative to get some sense of the key drivers of loyalty, which will differ from one category to another, and quantitative, to establish benchmark measures and conduct loyalty tracking studies.

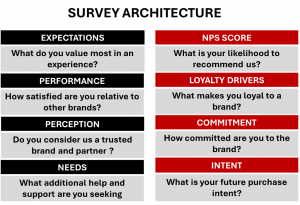

The survey architecture is critical. What you want to understand is the gap between the expectations of customers and how satisfied they are with their actual experience. You need to determine the relative importance to them of various facets of that experience. You also want to know how they perceive your brand versus the competition. And you should know whether there any important underserved needs you may not be aware of. But most importantly, you need to assess their level of loyalty, using both NPS as a measure of advocacy and a “commitment” score as a measure of loyalty.

The survey architecture is critical. What you want to understand is the gap between the expectations of customers and how satisfied they are with their actual experience. You need to determine the relative importance to them of various facets of that experience. You also want to know how they perceive your brand versus the competition. And you should know whether there any important underserved needs you may not be aware of. But most importantly, you need to assess their level of loyalty, using both NPS as a measure of advocacy and a “commitment” score as a measure of loyalty.

The commitment score is a composite metric made of weighted ratings on a 5 or 7-point Likert scale based on customer responses to a set of five questions:

- Would they miss the brand if it went away?

- Would they go out of their way to buy the brand?

- Do they prefer the brand to all other brands?

- Are they always willing to consider new products?

- Do they consider themselves a loyal customer?

The most committed customers are the true loyalists who give the brand top-box scores every time. The brand meets their needs. They can’t live without it. They have no interest in exploring alternatives. They care enough to go out of their way to buy the brand.

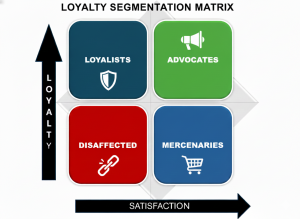

If you plot those customers on a 2×2 matrix with satisfaction and loyalty as the axes, you will find most of them clustered in the upper right quadrant: highly satisfied and highly loyal. And then if you profile their behaviour, you are likely to discover they are also your most valuable customers, the ones spending 3-5 times more than average, who have been around the longest, who are early adopters of new products, who don’t mind paying a premium, who rarely complain, who are the first to provide constructive feedback, who account for a disproportionate share of sales. Go further and profile them according to their interactions and they are also likely to be your most enthusiastic fans with the highest rates of community engagement.

If you plot those customers on a 2×2 matrix with satisfaction and loyalty as the axes, you will find most of them clustered in the upper right quadrant: highly satisfied and highly loyal. And then if you profile their behaviour, you are likely to discover they are also your most valuable customers, the ones spending 3-5 times more than average, who have been around the longest, who are early adopters of new products, who don’t mind paying a premium, who rarely complain, who are the first to provide constructive feedback, who account for a disproportionate share of sales. Go further and profile them according to their interactions and they are also likely to be your most enthusiastic fans with the highest rates of community engagement.

A Loyalty Strategy

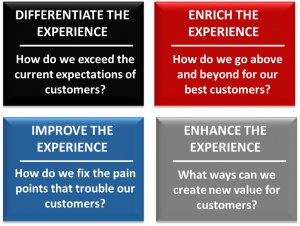

Now that you know how loyal customers really are, you need a customer relationship management strategy that not only sustains and deepens the loyalty of your most committed customers, but draws converts from the “malleable middle”. That’s why you need more than a loyalty program – you need a loyalty strategy. The starting point is not “How do we reward customers?”, but “How do we earn greater loyalty?”.

The strategy should be welded to an uncompromising principle of reciprocity: that is, the brand should be just as loyal to customers as they hope customers will be loyal to them. It’s a principle Fred Reichheld calls “The Golden Rule”. He points out, “Most NPS leading firms are Golden Rule exemplars, earning customer relationship net scores ranging from 50 to 70”.10 He goes on to say, “The primary purpose of a great business is making customers’ lives better”.

That purpose proclamation – how we make customers’ lives better – should be the strategic starting point. It should be unambiguous and heartfelt. It should be the organization’s North Star – a rallying cry that unites everyone around a common vision. Gives them a reason to be excited about the importance of the work they do.

“For most mature brands, 85 percent of revenue growth can be expected to come from the most loyal customers.”

For example, the beloved grocery chain Trader Joe’s proclaims: “We want our customers’ experience while shopping in our stores to be rewarding, eventful and fun. Every time a customer shops with us, we want them to be able to say, ‘Wow! That was enjoyable, and I got a great deal. I look forward to coming back!’.

Trader Joe’s does not offer a points program because its business model is exclusively focused on delivering a consistently positive shopping experience, quality products, and competitive prices. The strategy is clearly working: Trader Joe’s NPS score is 46 compared to an industry average in the U.S. of 27, up there with the other customer-first leaders like COSTCO, Aldi, and Wegman’s, all of whom operate according to a similar ethos.

Instead of customer management and retention being a secondary priority, as it is in most companies where “conquest” programs soak up the lion’s share of marketing dollars, the primary strategic focus should be on building lifetime relationships. After all, for most mature brands, 85% of revenue growth can be expected to come from the best customers.

Marketing’s main mission is to move customers along the relationship continuum from first-time buyer, to repeat purchaser, to brand enthusiast to committed loyalist by “making customers’ lives better“. The questions that guide this strategy should be: How do we give customers a more rewarding experience, not simply more rewards? How do we create continuous value for them so that they never have a reason to leave? How do we make them feel we always have their best interests at heart? How do we show our best customers the recognition and appreciation they deserve? How do we prove to them we’re on their side?

Winning brand loyalty and trust is entirely dependent on the promises that are kept rather than the ones that are made. So marketing must take ownership of the customer relationship while fostering a culture that puts customers first. Tough to do if there is any kind of misalignment between corporate values and customer-centricity. A relationship management program will be stillborn if a shareholder-first mindset prevails – if buy-in from the C-suite is not assured – if investments in CX get swept away at the first downturn in quarterly earnings. “Being good to customers is good for business” is the message that executives needs to hear, backed by a business case that proves the linkage between loyalty and the health of the business.

Winning brand loyalty and trust is entirely dependent on the promises that are kept rather than the ones that are made. So marketing must take ownership of the customer relationship while fostering a culture that puts customers first. Tough to do if there is any kind of misalignment between corporate values and customer-centricity. A relationship management program will be stillborn if a shareholder-first mindset prevails – if buy-in from the C-suite is not assured – if investments in CX get swept away at the first downturn in quarterly earnings. “Being good to customers is good for business” is the message that executives needs to hear, backed by a business case that proves the linkage between loyalty and the health of the business.

For most companies this transition from thinking about loyalty programs to thinking about making customers more loyal is not an easy one to make. It requires a radical mindset shift from short-term to long-term strategic thinking; from chasing new customers to increasing the value of existing ones; from taking customers for granted to treating them with care and respect; from buying loyalty to earning it.

For too long now, companies have lived under the illusion that customers are content to collect their program points and happily pocket their savings. But in fact customers want much more out of their relationship. They want their lives to be easier and more convenient. Even enjoyable and fun. But more than anything, they simply want to stop feeling “ripped off”.

Stephen Shaw is the Chief Strategy Officer of Kenna, a marketing solutions provider specializing in delivering a more unified customer experience. He is also the host of the Customer First Thinking podcast. Stephen can be reached via e-mail at sshaw@kenna.

1. “Loyalty Programs: The Complete Guide”, Philip Shelper, 2023 | 2. “Loyalty Management Market Report”, Market Data Forecast, 2025 | 3. “Canada Loyalty Programs Market Intelligence and Future Growth Dynamics”, The Retail Data, March 2025 | 4. “Canada’s top 10 loyalty programs and new usage trends”, Retail Insider, 2024 | 5. “Hotel Loyalty Programs Continue to Prove Their Value”, Hotel Online, 2025 | 6. “Forget a recession. Canadians are facing worse”, Globe and Mail, November 22, 2025 | 7. “Service Now Consumer Voice Report”, 2024 | 8. “The Relation of Consumers’ Buying Habits to Marketing Methods”,1923, Harvard Business Review | 9. The Dubious Management Fad Sweeping North America”, WSJ, 2019 | 10. “Winning on Purpose”, Fred Reichheld, 2021