By Stephen Shaw

By Stephen Shaw

The rapid growth of direct-to-consumer (DTC) brands may seem like a replay of the dot-com bubble in the Web 1.0 era. But what makes this new generation of DTC brands different is a genuine love for their customers.

They have infiltrated just about every consumer category—clothing and apparel, personal care, home furnishings, food and drink, travel, pet food—just to name a few. Hundreds of DTC brands, seizing market share from the big established consumer brands.

Known as “digitally native” brands, they are challenging every conventional idea of how to build a successful brand.

Many of these newly minted brands have become household names in just a few years. The mattress maker Casper has become synonymous with sleep. Warby Parker has transformed how eyeglasses are bought. Allbirds has become the hippest, comfiest sneaker in the market. Contact lens maker Hubble has freed lens wearers from paying extortionist prices. BarkBox delights pet-lovers with monthly deliveries of whimsical dog toys and treats. The clothing company Everlane has woven price transparency, ethical manufacturing and quality materials into one of the trendiest fashion brands in the market.

These brands, and many more, have rocketed to fame on the strength of their digital mastery. And they have won loyal fanbases by being “maniacally focused on the customer experience”, in the words of Bonobos founder Andy Dunn, whose online clothier company was inhaled by Walmart last year1.

Meeting the new customer ethos

It helps that people today crave simplicity and authenticity, especially that cohort group known as Millennials, who are soon to become the biggest spending consumer demographic. For one thing, they are the most willing to experiment with new brands. They are skeptical of corporate brands claiming to be social activists. They have a soft spot for rebels. And they are drawn to brands that show, rather than simply say, they care. As long as the brand is relatable, Millennials will make room for it, no matter how unfamiliar it may be.

That relatable ethos is what accounts for the meteoric rise of DTC brands. It is what sets them apart from the corporate incumbents. And it is that intimate relationship with customers which gives them a distinct advantage over brands dependent on distributors and retailers to showcase and sell their products.

Take Glossier, for example, the skin care beauty brand that became an overnight sensation, mainly by monetizing the fervour of its devotees. Glossier fits the definition of a social brand: maybe even an egalitarian one, open to ideas from anyone. Its adoring fans flock to Glossier’s Instagram site, where they eagerly post pictures of themselves using the products, share beauty tips and submit ideas (“2019 needs to be the year that @glossier finally puts out an eye cream”). They even petition to be a spokesperson (“I would LOVE to be a glossier REP! Please DM me if interested please”).

What makes this brand so beloved by its community of two million Instagram followers is its credo that beauty is a matter of individual style. As founder Emily Weiss explained, “Beauty has traditionally been brands telling customers that they have some kind of inadequacy or that they should ascribe to a specific idea of perfection. The insight that we had at Glossier was to encourage every woman to become her own expert”2.

Glossier has proven that the way to build a fanatically loyal community is to resonate with their world view, using social content to drive conversation, and then harness the feedback to develop products that customers will care enough about to promote amongst their own friends. “Content is really our heart and soul”, said Weiss.

DTC then, and now

That reliance on thoughtful content and a highly engaged community is common across most DTC brands. And it is why, unlike the early days of the commercial web, when there were just as many aspiring e-commerce start-ups, the prospects for long-term growth and success are so much more favourable.

The rapid ascendancy of DTC brands harkens back to the early web era (1994-1999) when a slew of venture capital (VC)-funded “dot-coms” emerged to “change the world”. What they actually wanted to do was “grow big fast” in a feverish sprint toward an initial public offering (IPO). And just like today, the VCs were pouring loads of cash into these early stage ventures, looking to make a killing the moment that IPO hit the street.

The rapid ascendancy of DTC brands harkens back to the early web era (1994-1999) when a slew of venture capital (VC)-funded “dot-coms” emerged to “change the world”. What they actually wanted to do was “grow big fast” in a feverish sprint toward an initial public offering (IPO). And just like today, the VCs were pouring loads of cash into these early stage ventures, looking to make a killing the moment that IPO hit the street.

Whether they were selling pet food, groceries, clothing, toys or furniture, these fledgling e-commerce companies aimed to become category killers. Their strategy was to gain first mover advantage: and in the Web 1.0 era that meant spending exorbitant sums on broadcast media to gain awareness. The goal was simple: build a large volume of web traffic in the hope that profits would (eventually) follow. And while that became true for Amazon several years after it was founded in 1998, the profits never did materialize for the vast majority of e-commerce companies, wiping out almost all of them in the 2001 dot-com crash.

As it turned out, that first generation of DTC companies was way ahead of its time. Apart from too few Internet users in those embryonic years, plus their own reckless urge to splurge on mass advertising, their downfall was mainly due to an inadequate logistical infrastructure. Back then it cost a lot to deliver products to the doorstep. And running an e-commerce operation came with a high computing overhead. So, as the losses began to mount, with no end in sight, investor confidence vaporized, setting the stage for sudden extinction.

What’s different today, of course, is that everyone now lives a digital life. People are conditioned —indeed demand—to do stuff online, preferably on their phones. A whole generation of digital natives has reached adulthood. And the infrastructure costs are a fraction of what they were in the mid-1990s.

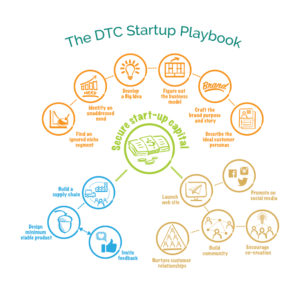

These days a start-up brand is able to maximize profits by controlling the entire value chain, from production to selling to distribution. They can easily piggyback on existing third-party infrastructure offered by such companies as Ottawa, Ont.-based Shopify, whose commerce platform supports everything from site design to order management and to fulfillment. All a start-up brand has to do today is come up with a Big Idea and, presto, they can be open for business in no time.

Looking for the long tail

Coming up with that jackpot idea is the trick. There certainly needs to be a compelling business case to attract seed funding, or at least the faint promise of eventual riches. But how do you find a virgin market opportunity when global enterprises with enormous research budgets like P&G and Unilever are on the constant lookout for new product ideas?

The answer is to look for unrequited needs in places the major brands steer clear of, namely, the so-called “long tail” of the market. Corporate brands are in the business of serving the “fat tail” of the market where the greatest sales volume can be found, since their business models require them to operate at scale, selling as much as they can to as many people as possible. Usually a niche market is just not worth pursuing for the relatively meager pay-off.

That makes corporate brands oblivious to under-the-radar segments that at first glance don’t warrant the investment. Which is exactly why many of the DTC brands are thriving. They found an underserved niche and came up with a winning idea by simply asking, “How can we help these people?”

Take Hims, for instance, launched in 2017. In just two years it has become the fastest-growing men’s wellness brand, catering to younger men suffering from premature baldness, erectile dysfunction, premature ejaculation or performance anxiety. Instead of skulking around a drugstore, searching for Rogaine, customers are given the option of consulting over the telephone with a qualified physician. Within minutes they can order medically prescribed products shipped directly to their home, saving them the embarrassment of buying in-store.

Hims’ lifestyle blog, Savoir Faire, tackles a wide range of personal wellness subjects, using a breezy, light, irreverent tone, just like two guys talking to each other (“You need erections when you want them, not when it’s convenient for your penis”). Whether it’s counselling guys to drink more rum, debating the merits of Cialis versus Viagra or suggesting how to fix your posture (“Let’s talk about posture, fellas. There’s a good chance yours could use improvement”), the idea is to open up a conversation about taboo subjects that most guys prefer to avoid.

Describing his formula for building a “unicorn” brand, Hims founder Andrew Dudum said, “You have to have incredible financials very early. You need diversity in revenue and customer. And you need loyalty and love that could last for 20-plus years”3.

Creating loyalty and love

When a new brand is born inside a big corporation, its origin story is hollow, usually an agency-conceived bit of fiction. The product is incubated in a lab—tested through focus groups, artificially grown through advertising—and survives only with the blessing of retailers. More often than not, the newly-launched brand fades from sight, ostracized by consumers.

Whereas a digitally native brand comes into the world with a genesis story based on the founder’s moment of epiphany. The brand’s reason for being becomes a motivational “North Star”, attracting early followers by positioning itself as a force for good. Customer affinity grows over time, earned through one positive experience after another, ultimately leading to “loyalty and love”.

Here is how Brandless, a highly successful DTC start-up offering affordable quality products, sees itself. On its web site it says “We’re creating a new kind of customer relationship by being in direct, two-way communication with the people who buy our stuff and the people who make our stuff. The whole Brandless organization is built around customer feedback, as we grow a community of people who believe everyone deserves better.”

These brands always take the side of the customer—not just by going out of their way to help them—but by standing up for what’s right. They lead by example, they show empathy, challenge orthodoxy, expose charlatans and price gouging, serve as advocates for social change and are transparent and are champions of sustainability and equality.

But most important, these brands eliminate the tedium and bother of shopping: serving as curators, concierge services, community hubs, confidants, “explainers” but mostly as simplifiers. “Less is more” is their universal motto: offering a limited selection of quality products, sold below retail price and shipped directly to the door.

Above all, these brands relate to their customers as a community of like-minded people, not “online buyers”. They make them feel part of something special—members of a tribe—and encourage them to connect with each other. They become natural extensions of people’s lives—a brand to be experienced—simple, easy, fun, approachable, inspirational, reassuring and risk-free.

Social-driven impact

All of these start-up companies, many of them only a few years old, have grown at the expense of legacy brands that have spent years, sometimes decades, buying their way on to store shelves while advertising through mass media just to get consumers to remember their name. The DTC brands have silently crept up on them, gaining a foothold in the market by using social media to reach highly segmented audiences.

And that’s the big difference from the dot-com era. Social platforms have given these brands an easy on-ramp: an option that simply did not exist in the late 1990s. If Facebook had come along a decade earlier, many of those forerunner brands would likely have survived the nuclear winter that followed the 2000 crash.

The hypertargeting offered by Facebook, Instagram and Twitter —and their ability to improve the conversion rate algorithmically through “lookalike” modeling —allows DTC brands to find the right audience at an affordable acquisition cost. Once a relationship has been activated (a clickthrough, a sign-up, a purchase), the network effect takes over, leading to referrals by customers keen to serve as micro-influencers. That’s how Glossier grew so fast, recruiting its most prolific co-creators to become brand ambassadors.

It is a formula that has caught the attention of classic marketers like P&G that are becoming less afraid of alienating their retail partners by going direct. But to recapture market share from digitally native brands, the large enterprises will have to do much more than imitate their social media tactics. Because the biggest advantage the DTC brands have is the loving relationship they have with their customers and a sincere resolve not to disappoint them.

Stephen Shaw is the chief strategy officer of Kenna, a marketing solutions provider specializing in customer experience management. He also hosts a regular podcast called Customer First Thinking. He can be reached via e-mail at sshaw@kenna.ca.

1 Andy Dunn, “The Book of DNVB”, Medium.com, May 9, 2016.

2 Amy Farley, “A Breakout Branding Master Class from Glossier, Sweetgreen, Away, And Walker & Co.”, Fast Company, January 12, 2018.

3 Hilary Milnes, “How Hims founder Andrew Dudum plans to build a $20 billion business”, Digiday UK, December 28, 2018.