By Stephen Shaw

By Stephen Shaw

Marketing is in crisis. No longer respected by corporate chieftains as a strategic function, it has been demoted to simply making ads. The only way for marketing to stage a comeback is to become a difference maker once again.

There was a time when people never thought twice about getting their drinking water from a tap. Or if they were outdoors, from a water fountain. Or in the office, from the large blue jug atop the water cooler.

That all began to change forty five years ago.

That was when Perrier, the top selling sparkling water in Europe, launched one of the most successful marketing campaigns of all time to crack the U.S. market. A series of TV ads featuring the sonorous voice of Orson Welles proclaimed the water to be “naturally sparkling, from the center of the earth”. His message resonated with a boomer audience seeking a healthy alternative to soft drinks and alcohol. The campaign just happened to coincide with the jogging craze that had started in the mid-1970s. Perrier began to sponsor running events everywhere.

Soon after the company’s distinctive green bottles began to fly off the grocery shelves. The rest of the beverage industry took notice, as the bottled water category grew rapidly, cutting into soft drink sales. Pepsi and Coke had no choice but to get in on the action. But instead of sourcing their water from aquifers and springs, they figured they could just take advantage of their existing purification equipment and turn ordinary tap water into something they could market as “pure”. They were able to exploit their sway over convenience stores to ensure their brands were given plenty of visibility. And thanks to their massive ad spending, their share of bottled water sales soon surpassed every other competitor.

By the start of this century the beverage industry had convinced most people that bottled water was healthier than what came out of the tap for free. And by associating the product with healthy living, the act of drinking bottled water signified an active lifestyle (until of course it eventually led to widespread revulsion over the mounting piles of single-use plastic).

The story of bottled water was a brilliant triumph of marketing — a classic example of “engineering demand”: convincing people of a need they never knew they had. Sure, people had to pay for water — but it was water that was “better” for you, “purer”, “tasted better” — all made-up claims, of course, completely debunked in independent water quality and blind taste tests.

At its best marketing can transform an entire industry merely through the amplification of an idea. At its worst it can lead people astray by promoting mindless consumption over the common good. And that’s where the marketing business finds itself today — at a fork in the road, facing a reckoning over past excesses while trying to validate its worth. Marketing is going through an existential crisis — challenged by corporate chieftains for its shallowness, viewed disdainfully by the public for deceptive practices, and yet knowing the only path to redemption is to do what’s right for customers and society, despite the relentless pressure to grow revenues. How marketing responds to this crisis will determine its future as a management discipline.

A Watershed Moment

Coca Cola was able to help pull off the clever trick of persuading people to pay for something that was already free because it has always been masterful at branding. The company has defied the laws of commoditization by making the Coke brand more valuable than the product itself, turning an otherwise ordinary fizzy beverage into a symbol of togetherness. Its most famous slogans — “It’s the Real Thing”, “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke” — lived on in memory long after the campaigns ended because they stirred the soul.

Coke has always excelled at stirring people’s emotions by associating its brand with universal themes like togetherness.

The actual secret formula to Coke’s popularity has been bottling consumer sentiment — wrapping itself in humanitarian themes like patriotism, social harmony, happiness, and solidarity — and then spinning that into advertising gold. Coke realized early on that memorable advertising is about making people feel happy. Just recall those Christmas-time ads featuring a rosy-cheeked Santa Claus with his bottle of Coke — or Mean Joe Greene of the Pittsburgh Steelers sharing a Coke with a young fan. And so when the beverage giant announced last year that it was “transforming and modernizing” its marketing model by moving away from mass communication, it was a watershed moment.

Here we have a 130-year old company that spends $5 billion per year on feel-good communications announcing that it was backing away from the very strategy that had made it one of the most valuable brands in the world. Instead Coke wants to create “unique and ownable experiences”, in the words of its CMO, developing an “ecosystem of experiences” aligned with “consumer passion points”. The announcement of its new branding platform “Real Magic” was a clear sign that marketing is at a turning point.

Coke realizes that scrawling “happiness” messaging on media walls everywhere is no longer enough to prop up even an iconic brand. More has to be done to connect with a public whose lives are ruled by their screens. Never before have people been able to crowd out ad messaging by creating, publishing, and sharing their own content. But this democratization of media, leading to a content glut and the fractionalization of attention, has radically altered the marketing landscape, making the kind of tentpole campaigns that Coke became famous for dead-on-arrival.

Everyone knows that people are not consuming media the way they used to — certainly not anyone under the age of 25 who spend their time on Twitch, TikTok, YouTube, Instagram and Snapchat. How do you get through to a perpetually distracted generation with miniscule attention spans when they are far more interested in sharing their own stories? Who prefer streaming video to TV? Whose free time is taken up playing games? Who want to connect with their friends, not brands?

Coke has embarked on a grand experiment in platform storytelling to “change the way it communicates with consumers”, a transformation every other marketer now faces as well. The marketing playbook for this transformative era is being written on the fly, by Coke, by Nike, by Red Bull, by Proctor & Gamble, by any number of DTC start-ups, by any brand, in fact, that realizes the jig is up: the Age of Persuasion is over.

Historically, marketing has proven to be remarkably adaptable in the face of revolutionary change, the first to confront upheavals in consumer habits, in media usage, in cultural norms, in societal expectations. The main job of marketing, in fact, has been to seize upon those trends and convert them into commercial opportunity. But the market climate that exists today is far more complex and forbidding than at any time in the past, threatening marketing’s very existence as a business function. Who needs marketing anymore if no one is paying attention to ads? If people see ads as just more fake news?

The “Hidden Persuaders”

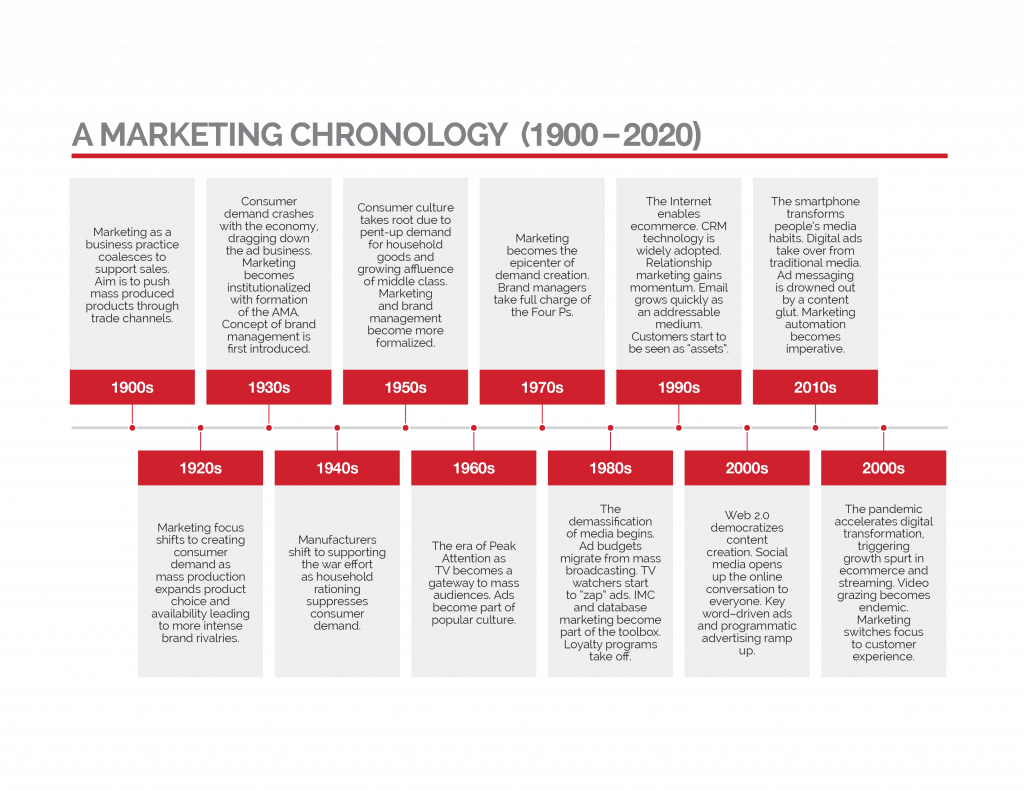

Marketing never used to be just about making ads. Certainly not in the early 1900s when marketing initially began to take shape as a management practice. Back then marketing was a verb and not a noun. It was a time when new mass production methods had created standardized products in large volumes which could be distributed and sold nationally for the first time.

The first marketing textbook published in 1914 defined the new term “marketing” as inclusive of everything to do with influencing sales.

In this formative period the terms “marketing” and “distribution” meant the same thing. Manufacturers counted on wholesalers and distributors to find them buyers. Marketing was all about how to take products to market through intermediaries. The first textbook to even have marketing in the title — “Marketing Methods and Salesmanship” — did not appear until 1914. The authors of that book wrote that in place of ‘selling’ the word ‘marketing’ is “gradually coming into popular use to apply generally to the distributing campaign.” They go on to explain, “Marketing methods, in a sense, are inclusive of everything that is done to influence sales”.

By the 1920s, manufacturers needed to fill the rapidly expanding shelves of chain stores that had begun to displace local shopkeepers. Brand rivalries erupted as manufacturers battled for shelf supremacy. Whether selling soap or breakfast cereal or toothpaste, “reason why” advertising was their way to crow about product differentiation (“Kitchen Work Is Now a Pleasure!”). Advertising was synonymous with salesmanship.

Owing to greater prosperity and free time, ordinary people felt they could now afford modern household gadgets and newly invented electric appliances, even radios and automobiles. It was the start of consumer culture. That is, until the party abruptly ended in 1929, bringing the Roaring 20s to a crashing halt. The ad business cratered along with the demand for products.

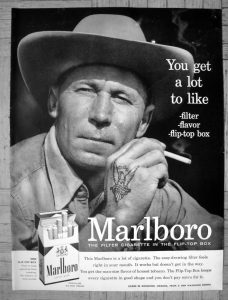

In the 1950s and 60s marketing campaigns became part of the culture, creating iconic figures like the “Marlboro Man”.

Despite the worldwide depression, marketing became institutionalized during this era. In 1931 P&G’s Neil McElroy famously came up with the idea of brand management. And in 1935 the National Association of Marketing Teachers, a forerunner of the American Marketing Association, crafted the first definition of marketing: “Marketing is the performance of business activities that direct the flow of goods and services from producers to consumers”, amended slightly in 1937 by the newly formed AMA to read: “…the flow of goods and services from production to consumption”. This original definition stood for the next half century.

Once the world emerged from the wartime years in 1945, consumer demand for products awoke from hibernation after nearly two decades of thrift, deprivation, and rationing. The manufacturing industry went back to full-scale production of consumer goods. The boom times began. The “baby boomers” came along. The car-friendly suburbs metastasized. Shopping malls began to spring up everywhere. An increasingly affluent middle class strived to “Keep up with the Joneses”. Conspicuous consumption became a way of life — luxury goods a status symbol — social conformity an expectation.

By the early 1960s there were TVs in every home. Massive audiences tuned in to watch the same few network shows (“I Love Lucy”, “Gunsmoke”, the “Ed Sullivan Show”). Advertisers salivated — mass advertising was now possible. Ads became part of the culture: “The Marlboro Man”; the “Jolly Green Giant”; the “Pillsbury Doughboy”. Campaign slogans and jingles became as familiar as top billboard songs (“You’ll wonder where the yellow went, when you brush your teeth with Pepsodent!”). These were the Mad Men years — the era of Peak Attention.

It was during this golden age of mass media that marketing became widely accepted as a legitimate discipline. The turning point came in 1957 with the publication of John Howard’s “Marketing Management: Analysis and Decisions” which asserted that marketing could only be considered successful if it resulted in a sale. Three years later, in another inflection point, Edmund McCarthy introduced his famous Four Ps model in a book called “Basic Marketing: A Managerial Approach”. His model became the unifying theory for modern marketing.

This period was also when motivational research came into play, revealing the latent reasons behind consumer behaviour (a practice eventually exposed in Vance Packard’s 1957 sensationalist book “The Hidden Persuaders” showing how people’s subconscious minds were being subliminally manipulated by advertisers). It was also when the concept of brand image was introduced, suggesting that people’s visceral perceptions of a brand trumps rational thought. That insight changing the ad game, sparking a “Creative Revolution”: fact-filled ad copy was swapped out for imagery that triggered an emotional response. And for the first time market segmentation became a recommended stage of the planning process. But it was Phil Kotler’s 1967 classic textbook “Marketing Management — Analysis, Planning and Control” that proved marketing was a grown-up business practice, going on to become a standard part of the teaching curriculum for decades to come.

The End of Business as Usual

By the 1970s marketing management was fully in charge of the brand mix (the Four Ps). This was particularly so in the consumer packaged goods sector where the “best and brightest” business students flocked to do their marketing apprenticeship. Later they fanned out across other industries, bringing with them everything they had learned about brand building, with its emphasis on research-led market analysis and planning.

Mass advertising was still the go-to-market strategy. The glamour media channels (TV and print) absorbed most of the ad dollars while all other media (e.g., product sampling, promotions, point-of-sale display, sponsorships, direct mail and more) got whatever budget scraps were left over. Heading into the 1980s, however, that was all about to change.

The biggest disruptive force was the rise of cable TV. Traditional network TV began to lose its captive viewers to Pay TV channels. The audience diaspora began. And it was during this same period that VCRs (succeeded later by PVRs) suddenly exploded in popularity. People could now time shift their viewing — even better, “fast forward” through ads. As the decade rolled on these forces of “demassification” led to close scrutiny and questioning of traditional advertising. Mass audiences were becoming too hard to reach. Concern grew over the cost and effectiveness of mass advertising. Marketers began to spread their dollars more equitably across different forms of media in an effort to create fully integrated brand communications (‘IMC’ for short).

By the mid-1980s a new, more targeted media alternative was becoming technically feasible: the use of addressable databases to target specific individuals. Database marketing became a fast-growing speciality function. And as desktop computing became more accessible, for both businesses and consumers, marketing automation systems grew in number alongside early CRM and SFA solutions designed to automate customer service operations and sales forces.

At the same time a new school of thought began to emerge in academic circles (championed by prominent scholars like Jagdish Sheth and V. Kumar), going on to become the bedrock principle for relationship marketing: namely, the idea that sustainable growth is only possible by getting closer to customers. Customers are assets, its proponents argued, whose future cash flow was vital to the health of a business. More attention and resources needed to be spent identifying and retaining the high value customers because, the logic went, it cost much less to keep a customer than acquire a new one.

That idea crossed over from academia into the mainstream in 1993 with the best-selling book “The One to One Future” by Don Peppers and Martha Rogers. They urged marketers to give up expanding “share of market” in favour of “share of customer”. Written just a couple of years after the birth of the Internet, the book depicted “life after mass marketing”. Soon after, the term “one-to-one” marketing became an everyday expression.

Through the 1990s the adoption and growth of CRM was stalled by old school forces resistant to change. But by the time the new millennium arrived, there was no turning back. The exponential growth of the World Wide Web eventually led to a rising movement to reform marketing amongst a messianic class of digital marketers. They were determined to challenge orthodoxy and shake up the status quo. The most compelling expression of that reformist ambition was “The Cluetrain Manifesto”, a treatise published in 2000 that boldly decreed, “the end of business as usual”. The authors asserted, “Markets are conversations”, and argued that the only way business could join the conversation was by speaking with a “human voice”.

Following the dot-com bust in 2000, Internet technology progressed from serving up static pages that were meant to be passively read (Web 1.0) to a more interactive medium where people could actively participate by creating and sharing content (Web 2.0). But it was the launch of Google AdWords, followed by the meteoric rise of programmatic advertising in the mid-2000s, that catapulted marketers into the digital age. Marketers had to begin thinking about how to allocate their budgets across earned, owned and paid media. Every business now had a marketing team solely dedicated to digital media.

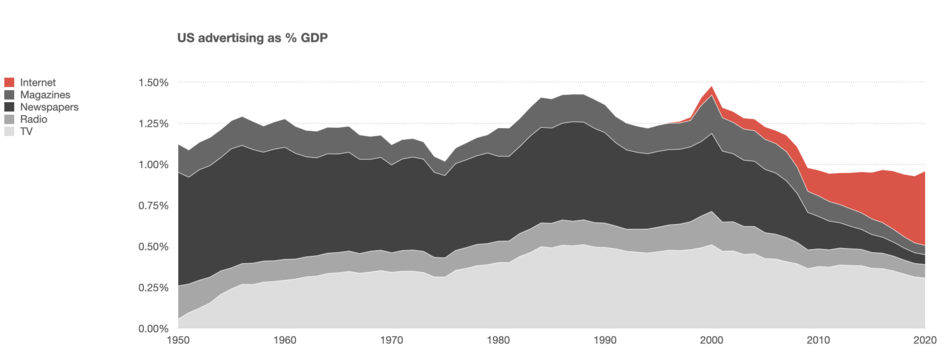

What followed was even greater media fragmentation and a sharp fall-off in the size of TV audiences and print readership as people drifted away from conventional sources of information. Their smartphones were now commanding most of their attention. Marketers began to divert a big slice of their media budgets from offline to online — mainly using Google and Facebook — which they would continue to do year after year until in 2019 it would finally surpass traditional TV and print spending. In that time marketing spending on social media doubled, suctioning up more than one fifth of the total marketing budget in pursuit of “followers”, “likes” and “shares”.

An Alien Landscape

In 2004 the AMA decided that the contours of the marketing landscape had changed sufficiently to warrant a fresh look at its definition of marketing which had gone unchanged since 1985. That earlier definition still viewed the discipline as primarily a mercantile transaction between seller and buyer with marketing management in charge of the 4 Ps. But there was no mention of the customer. So the AMA came up with a new definition that reflected the growing importance of relationship marketing: “Marketing is an organizational function and a set of processes for creating, communicating and delivering value to consumers and for managing relationships in ways that benefit the organization and its stakeholders.”

In the 1950s and 60s marketing campaigns became part of the culture, creating iconic figures like the “Marlboro Man”.

Source: “TV, merchant media and the unbundling of advertising”, Benedict Evans

The revised definition came under fire from critics who felt that the job of facilitating an “exchange” should never have been left out. Plus, they argued, marketing had a moral imperative to do what’s right for society, not just for the organization. So the definition was amended in 2007 to read: “Marketing is the activity, set of institutions and processes for creating, communicating, delivering, and exchanging offerings that have value for customers, clients, partners, and society at large”.

Ever since, marketing has been buffeted by the centrifugal forces of data, technology, media diffusion and, more recently, public distrust. Marketers are now witnessing the most dramatic shift ever in consumer buying behaviour, lifestyle, media habits and values. The marketplace has become an alien landscape. The media business is disintegrating. People are fleeing from intrusive brands; will do anything to avoid ads; ache for greater meaning and purpose in their lives. Sustainability is a worrying concern — so is social justice — so is the need for more conscientious consumption. Lifestyles are in flux, due to the isolating impact of the pandemic. Brand trust is harder to win than ever. And video streaming and gaming are preoccupying an upcoming generation of socially connected GenZers (now called “zoomers”) who shun TV watching.

Stripped of its broader powers to influence corporate strategy by the financialization of business decision making, with its myopic emphasis on short-term profits, marketing is now populated by digital natives who have limited job qualifications and no clue what marketing strategy really means. The popular Marketing Week columnist Mark Ritson acidly notes that “Half of all marketers don’t have any knowledge of marketing. No training. No big picture. No real clue.” Their employers expect them to learn on the job — except that any senior mentors who might have been able to coach them are long gone, victims of the naïve notion that marketing is a job anyone can do (preferably, someone cheaper).

So now marketing is pretty much left with overseeing advertising and promotion, staffed by novices, who are “mediocre thinkers” rails Mark Ritson. Typically communication grads, they are unschooled in business planning, uncomfortable with numbers, lack analytical acumen, and care more about how an ad looks than brand positioning. They tend to be ignorant or dismissive of any marketing theories that predate the Internet (Phil who?). No wonder marketing has little say anymore in how the business is run. In fact, according to Forrester, just 35 percent of CMOs are involved in corporate strategy development. They are certainly denied a voice at board meetings.

As a result, CMOs have become expendable. Under pressure to drive sales, they are quick to be blamed for revenue shortfalls, even if the business is suffering for reasons beyond their control. Cranking up the ad volume is no longer the answer to a dip in sales. As the marketing consultant Mark Schaefer has said, “Most executive teams expect marketing to be coin-operated. You put coins in, you get more coins out”.

Long-term brand building has been sidelined by hard-selling click-to-buy digital tactics. Performance marketing has taken over, fixated on the bottom end of the sales funnel. Marketing has devolved into a motley crew of factionalized teams (social, mobile, email, paid search, CRM), vying for top gun status, protective of their turf.

Elsewhere in the business no one really understands what marketing does anymore — because neophyte marketers tend to get drawn to every passing fad, every shiny new object (NFTs being the latest infatuation). And with their baffling jargon, marketers seem to be living in an alternate universe. In short, marketing has lost whatever gravitas it once had. And so CEOs have started to question its purpose, unable to relate to marketing’s media-centric, superficial strategies. “Where’s the payoff?” they demand to know. “Why are likes even important?”.

How can marketing reclaim the leadership role it once enjoyed during that three-decade span from the 1950s to the 1980s? How can it live up to the idealistic call of digital utopians to “join the conversation”? How can it “make marketing great again” by focusing on creating genuine value for customers? How can it design and deliver rich, memorable, commercial-free experiences that will inspire, rather than bamboozle, their audiences?

It Always Starts with Innovation

Marketers should draw their inspiration from the brands that have proven to be the most resilient through each successive consumer era, adapting smoothly to continuous mutations in people’s media habits and buying preferences. And certainly one brand that deserves very close inspection — a brand that anticipates and shapes consumer demand rather than chase it — is the company that gave birth to sneaker sub-culture.

The story of Nike’s rise to become the world’s largest seller of athletic footwear and apparel provides an almost flawless blueprint for market differentiation. Consider how Nike started out — the co-founder Phil Knight selling imported Japanese running shoes out of the back of his car at track meets, up against shoe titans Adidas and Puma. Today Nike is a $44 billion company — its “swoosh” recognized worldwide — its enduring slogan “Just Do It” shorthand for athletic tenacity — its brand a symbol of exceptionalism. Nike found the sweet spot at the intersection of sport, culture, and fashion, leaving its once formidable adversaries trailing far behind.

The story of Nike’s rise to become the world’s largest seller of athletic footwear and apparel provides an almost flawless blueprint for market differentiation. Consider how Nike started out — the co-founder Phil Knight selling imported Japanese running shoes out of the back of his car at track meets, up against shoe titans Adidas and Puma. Today Nike is a $44 billion company — its “swoosh” recognized worldwide — its enduring slogan “Just Do It” shorthand for athletic tenacity — its brand a symbol of exceptionalism. Nike found the sweet spot at the intersection of sport, culture, and fashion, leaving its once formidable adversaries trailing far behind.

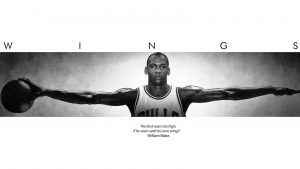

Nike got off to a fast start in the early 1970s by coming out with innovative new products that star track athletes were willing to wear and enthusiastically endorse — believing the shoes made them faster, more confident, more successful. Those high-profile endorsements won the attention of retailers who excitedly made room on their shelves for Nike’s orange shoe boxes. And then in 1984 Nike struck endorsement gold by taking a gamble on a rookie NBA player by the name of Michael Jordan. His shoeline, the Air Jordans, went on to become an instant hit. Later it spawned sneaker culture. But Nike’s innovative spirit was never limited to shoe design — it permeated every aspect of their business, especially their marketing. “For us, it always starts with innovation,” the CEO John Donahue wrote in his 2021 Shareholder letter.

Nike does just about everything right. Its shoe products are high quality. It’s stores are experiential meccas for wannabe athletes. Its apparel has street swagger. Its ads are always uplifting — its slogans memorable catchphrases (“There Is No Finish Line”). Its devotion to social justice is unflinching even in the face of critics. Its imprint on popular culture is profound. But there is one thing Nike does better than almost any other brand next to Apple: form a cultish attachment with customers bordering on worship. Just think of those sneakerheads who cherish their beloved collection of Nike shoes.

The Nike brand is an affirmation of the talent potential within everyone: “You too are an athlete capable of greatness”. All of its brand imagery and messaging is consistent in conveying that exceptionalism (just think back to “Wings”, the fabled 1980s Michael Jordan poster that hung on every young athlete’s bedroom wall). Nike doesn’t just sell products – it tells inspirational stories. Those stories imbue their products with an aura of exclusivity. It’s the reason Air Jordans continue to be a top-selling line for Nike: wearing them makes people feel special, whether they are worn for street ball or just hanging out. Everyone wants to “be like Mike” — exceptional.

Nike has also had the foresight to accommodate the omnichannel shopper — the mobile-first, “help me now”, socially engaged, butterfly consumer. At Nike’s 2022 Q1 earnings call with investors, the company’s EVP and CFO Matt Friend said, “As we accelerate our consumer-led digital transformation, we are developing and refining new capabilities that are transforming our operating model, quickly becoming a competitive advantage.”

Nike has invested heavily in developing high-performance digital commerce platforms. Today digital-sourced revenue accounts for 20 percent of its business — and that is expected to grow to 40 percent in a few years due to a fast-growing membership base of 300 million who rely on their mobile apps to guide their training activity, get tips and advice, participate in a community, share their achievements, and be the first to learn of new products and special offers. As a result, Nike has felt emboldened to pull its products from the shelves of middling retailers in favour of strategic partners who share their passion for sport.

Making a Difference

The sorcery behind Nike’s extraordinary ascent — the conjoining of innovation and marketing — is exactly what legendary business consultant Pete Drucker once declared were the only two basic functions of a business. Marketers everywhere should be encouraged by that evidence, knowing there is a larger role for them to play as a difference maker.

The next few years will be portentous for marketing. Ad spend as a share of GDP has already shrunk by one third. Pay TV is in freefall due to “chord cutting” — print advertising has nearly hit bottom — a “cookieless” Internet will suck the oxygen out of digital advertising — social media has become radioactive — so where will marketing spend its media allowance? Will it even be allowed to keep that allowance? Probably not. According to Gartner, marketing budgets as a percentage of revenue fell sharply last year from 11 percent to 6 percent, often reallocated toward digital transformation projects.

Despite the tornado warnings, the forecast is not entirely dire. The convergence of media, mobile payments and e-commerce is bound to open up all kinds of virgin opportunities (just look at how social channels have already transformed shopping in China). Merchant media platforms are growing — connected TV will enable individually targeted ads based on viewing and purchasing history — of course, there is also the “metaverse”, somewhere in the near future. After all, people still want to discover new products that can help them live a better life. They still want to browse and shop. Consumer culture still rules.

The starting point, as always, is innovation, as Nike points out. Marketing must use its creative superpowers to imagine what tomorrow looks like and come up with a strategic roadmap to navigate change. How can the business move at the speed of customers? How can it deliver even greater value? How can it be a trendsetter, not just a trend spotter? How can it be more integral to the lives of people? How can it prepare for the next generation of customers?

Marketing should serve as a divining rod for the business: become a cultural decoder — an alchemist capable of turning observations of human nature into insight. As marketing sage Scott Galloway has observed, “The CMOs who are thriving and potentially become the next CEO are the ones who say, ‘I’m your link to the market, I understand strategy’”.

Marketers will need to lead with empathy — learn what’s in people’s hearts, what excites them, what they care about, what troubles them. They must then link that insight to brand purpose and promote the ethos of putting customers first. Because the path to brand affinity now runs through people’s values. Most people crave identity and belonging – they hunger for connectivity with like-minded people. So marketers will need to go beyond creating “ecosystems of experiences”, as Coke has set out to do, to inspiring movements arising from a collective sense of purpose, as Nike has done. And that will allow marketing to get closer to people — to speak with a human voice — to tell stories that really matter to them.

Above all, marketing must stretch its mandate and own the customer experience – not just the initial stages leading to sale, the so-called “brand engagement” part – but all of it. The post-sale experience a company provides today is just as important a differentiator as its products and services. A bad experience will usually disqualify a brand from future consideration. So marketing should not simply serve as the brand custodian — turning its back on the customer once the sale is made – it should be the mastermind behind the entire customer journey. And that journey must be designed and orchestrated with one goal in mind: create customers for life. Win their trust. Convert them into brand believers. Enrich their lives. Because marketing’s job is not just about ad-making anymore: it needs to be about making a difference.

Stephen Shaw is the Chief Strategy Officer of Kenna, a marketing solutions provider specializing in delivering a more unified customer experience. Stephen can be reached via e-mail at sshaw@kenna.ca