By Stephen Shaw

By Stephen Shaw

Social media is on the cusp of a new era as people retreat behind closed doors to join private groups where they can safely interact with their trusted circle of family and friends. Marketers will have to reset their social strategies and intensify their efforts to form communities of interest amongst brand enthusiasts.

It was a time of extreme partisanship. The ruling class had split into two warring factions. Each side subscribed to a world view that was anathema to the other. They hurled false accusations at each other. They spread disinformation. They stoked feelings of indignation and outrage. All for the purpose of rallying the public to their side, using a new form of media.

It was called the printing press.

The time was 1660. The British Civil Wars had erupted. In the battle for public opinion, both sides had weaponized their words. The population was flooded with us-versus-them news, pamphlets, broadsheets, and posters, fanning the flames of conflict. Eventually the Parliamentarians gained the upper hand and King Charles I was beheaded.

As Shakespeare wrote, “What’s past is prologue”. A similar dynamic is going on in the present era — the same divisiveness, polarization, extremism, and uncontrolled spread of misinformation — the only difference being the form of media. Today the war of words is being waged through social media. And just as the printing press loosened the grip of the Royalists on freedom of expression, ordinary people have snatched the megaphone away from the press barons.

As liberating as that might have felt in the early days of social media, the slow demise of broadcast journalism since then has had a corrosive effect on social cohesion and people’s trust in each other. The initial promise may have been morally uplifting — who can object to “connecting the world”, or “giving everyone a voice”, or “speaking truth to power”? — but the result has been a blight on society. Idealists had hoped social media might lead to social change — just not the kind we ended up with. Epidemic loneliness, teen suicide, social strife, institutional mistrust, fear mongering, online bullying, “doxing”, conspiracy peddling, shrunken attention spans, you name it — the list of pathologies is long. Even the U.S. Surgeon General has concluded that compulsive use of social media can cause “profound harm to mental health” amongst young people.

Most people like to pin the blame on the tech overlords and their demonic algorithms. But while it is easy to accuse the social platform owners of mendacity — of knowingly exploiting human nature to make their fortunes — they could never have anticipated the destructive forces they were unleashing. And that is because they never paused to consider our dualities as human beings — our Jekyll and Hyde nature, capable of being kind and cruel, of good and evil.

According to anthropologists our tribal ancestors survived because they learned to band together and hunt in groups. They were reliant on each other for sustenance and protection. Gaining communal trust was a matter of life or death. But they were also wary of outsiders. They viewed neighbouring tribes as rivals — as people “not like them” — undeserving of compassion. And so they dehumanized them. That explains why warfare was endemic to all tribal societies. And these paradoxical impulses remain very much a part of our human condition today.

Sociologists will tell you that from the moment we come into this world we fear abandonment. We dread social isolation. We are emotionally dependent on the approval of others close to us. Our identity is derived in part from our affiliation with the various groups that form our social circle — from our relationships with people whose lives overlap with our own.

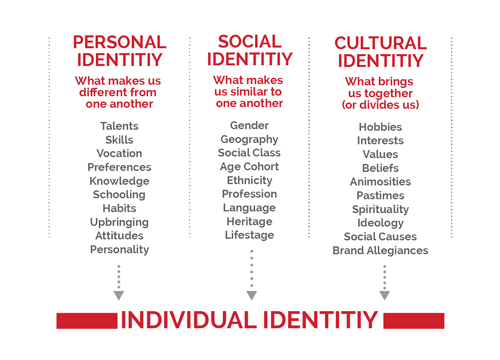

Figure 1 – A person’s identity is a fusion of what makes them different as individuals and their conformance with group values and norms.

It is this instinctive need for belonging — for affirmation — for recognition — that we tend to overlook as marketers. It is why we often fail to strike an emotional connection with customers. We objectify them, label them consumers, see them as “targets”, refer to them as “users”. And we focus too much on personal identity — the traits that make individuals distinct — rather than taking into account their social and cultural identities — the shared values, beliefs and allegiances that bring people together. Very few people are truly autonomous thinkers — their belief systems tend to be based on what other people like them think. They often turn to those same people — the people they trust the most — for help making decisions. Yet our marketing strategies are always based on personal identity, when it is social identity that leads to meaningful conversation.

Social media is not the source of all evil. It just mirrors our society. Our paradoxical nature. And that calls for rethinking its role in how we choose to connect with people. Marketers need to stop thinking of social media as an instrument of manipulation — as just another way to expand ad reach under the guise of having a conversation — as merely another part of the media mix — and start to view it as the main way to earn people’s trust.

Their Better Selves

Uploaded for all to see was a smartphone picture of a woman intentionally failing to pick up the excrement her dog had just deposited on a neighbour’s lawn. The social media post read simply: “This person’s dog took a big dump on the lawn, and she walked away merrily knowing what her dog had just done. What is your opinion on this?”.

The question elicited the expected tut-tutting from sympathetic neighbours. “It is disgusting”. “People that don’t pick up after their dog shouldn’t have one”. “You observed an irresponsible pet parent”. Other reactions were spiteful: “Dump her poop on her lawn”. “Pick it up, follow her home and tie it to her door handle.” “Wait till she passes again and throw it in her face”. And then inevitably a few contrarians chimed in: “Devil’s advocate here, she may not have had a baggie”. “Annoying for sure, but hardly worth getting one’s knickers in a knot”.

That “scoop your poop” post appeared on the global platform Nextdoor which connects neighbours with each other. The thread is typical of the reactions that even the most banal post can draw. And the comments came from people whose actual identity is known — it is a condition of membership — which disproves the notion that stripping away anonymity on social media will compel people to be more civil.

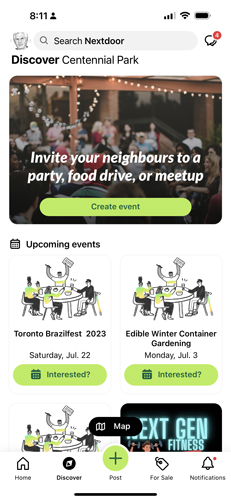

Figure 2 – Despite its mission to help neighbours show kindness to each other,

the conversations on Nextdoor can be just as

toxic as other social networking platforms.

Nextdoor had the noblest intentions when it started out in 2011. The platform founders wanted to make it easy for people living near each other to publicize local events, buy and sell stuff from each other, exchange information and tips, seek out recommendations and advice, connect with local businesses and much more. Certainly a viable concept, given the likely interest of local businesses in reaching nearby customers. But the founders of Nextdoor mistook proximity for neighbourliness. They counted on volunteer moderators to suppress any nastiness that might surface. But that job of moderation turned out to be overwhelming. As the CEO Sarah Friar has said1: “The challenge we deal with every day is moderating engagement to nudge people to be their better selves”.

Scrolling through a Nextdoor newsfeed you will find a continuous stream of posts on the most mundane topics. Lost pets. Gripes about prankster teens. Reports of suspicious characters lurking about. Coyote sightings. Plenty of crime reports about stolen vehicles, sometimes accompanied by home security video of actual thefts in progress. And mixed in with all of that: political screeds, racial profiling, dog whistling, rants about unkempt properties and litter in the park — rants about a lot of things — so many, in fact, that NextDoor has been mocked as a “snitch line” and a favourite hangout for “Karens”.

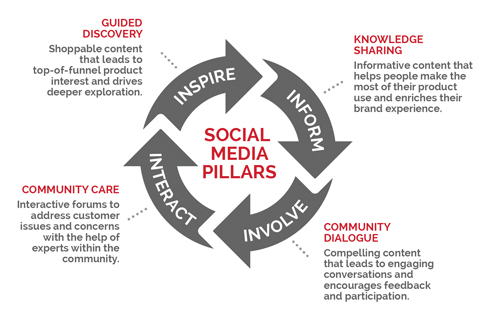

Figure 3 – The goal of a social brand is to form long-term relationships with people through authentic conversation and community.

The irony is that the Nextdoor mission is “To cultivate a kinder world where everyone has a neighbourhood they can rely on”. Yet despite the tirades and scaremongering and finger-pointing, the platform has managed to build a monthly active user base of 55 million members in eleven countries — 260 thousand neighbourhoods in total — who are clearly finding value in the platform despite the toxicity. Members find it can be quite comforting to receive concerned feedback and advice from people just being their “better selves”. Post a picture of the mess left behind by marauding raccoons, for example, and an avalanche of critter control tips is bound to follow. Members can also form private and public groups around topics of mutual interest, like dog ownership, neighbourhood improvement and parenting.

Nonetheless the problem remains: How do you minimize acrimonious and contentious conversations without suppressing free speech? How do you encourage members to abide by a code of conduct? How do you keep out the trolls? How do you make people feel safe from the fear of being bullied, shamed and chastised online? How do you intercept bogus information before it has a chance to metastasize?

The Facebook Trance

None of those questions occurred to Mark Zuckerberg when he first came up with the idea of a social media “utility”, as he called it then, for college kids on campus to connect with each other. He had inadvertently tapped into the deep desire of people to be socially connected and just as important, their subconscious longing for approval. Even then he wasn’t quite sure what he had invented — just another online directory, or something truly special? One thing for sure: it turned out to be a powerful narcotic, hooking users on jolts of dopamine with every news scroll.

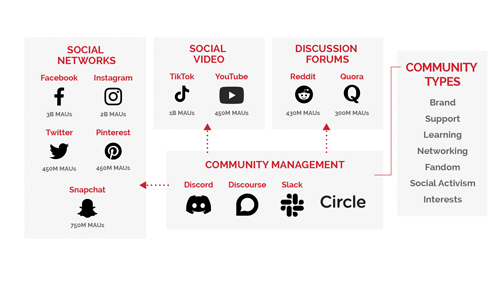

Figure 4 – The social media ecosystem is made up of both public and private platforms designed to connect people with each other.

By the time Facebook opened up its doors to everyone in 2006, Zuckerberg’s professed “social mission” was to “make the world more open and connected”. But Zuckerberg was (and still is) a hacker at heart. Hackers are really good at cracking the code on technical challenges. They are, however, unschooled in social psychology (except perhaps for gamification). Their line of sight extends only as far as the screen in front of them. And what Zuckerberg envisioned was certainly not as high minded as his social mission would suggest: He recognized the business opportunity to build an empire of engaged users who would be a dream audience for any advertiser. In short, he saw it for what it was: nothing more than a media business. But he cloaked that ambition in humanitarian ideals.

Today Facebook has three billion members around the globe, making it by far the largest social media platform. The sheer scale and might of it has made it the bête noire of privacy advocates and regulators. The singular mission of Facebook was never to facilitate connectivity — that was always a cover story — it was to drive engagement based on what people clicked on and how often. And Facebook’s appetite for data was so gluttonous that the company regularly stalked people as they roamed the Internet, amassing a vast trove of individual browsing information coveted by advertisers.

Through nearly two decades of empire building, Facebook (now called Meta) has pursued growth at all costs. The company has been guilty of committing one breach of consumer trust after another; it has warped how people interact with each other; it has distorted reality by manipulating its newsfeed to conform with the worldview of people; it has looked the other way as fake news was amplified and propagated, all the while denying liability by claiming to be merely a distribution channel; it has permitted bad actors to form hate groups and create pages that foment violence; it has allowed foreign powers to interfere in democratic elections. And along the way it hijacked the job of news curation to become the only source of information for one fifth of the population2 who just want to believe what they believe.

This all began in 2012 when Facebook first clued in to the psychology of engagement. In his Founder’s Letter that year Zuckerberg wrote that “Facebook aspires to build the services that give people the power to share”. In doing so he hoped to “rewire the way people spread consumer information”. By then Facebook had realized that people were competing for “views” and “likes” in their posts. A post that was “liked” would show up higher in the newsfeed of others, thereby creating a “validation feedback loop”3. The more attention that post got — the more views, the more positive comments, the more likes, the more emoji hearts — the better people felt about themselves, and the more likely they were to keep sharing. And that ultimately meant people spending more time on Facebook, scrolling, clicking, liking, posting, over and over again — the so-called “Facebook trance”.

Today Meta is under siege on multiple fronts. Privacy advocates have caught on to their deceptive data practices. Anti-trust regulators are breathing down their neck. Apple’s IOS now obliges Meta (and all other apps) to ask its users for permission to track their data. And its audience demographic is quickly aging. A whole new generation has come along since Facebook was founded which views it as a platform for their elders. Organic reach for brands keeps shrinking while engagement levels decline (now at an all-time low of 0.06%4), dragging down ad revenue with it. No wonder Zuckerberg has pivoted, sinking billions into his “fever dream”, as Scott Galloway puts it5, of a Quest-driven metaverse.

Zuckerberg has plenty of cash to figure things out. Privacy-first appears to be his new mantra. He has acknowledged that “the future is private”6, and that he is committed to building a “privacy-focused messaging and social networking platform”, which will be “even more important to our lives than our digital town squares”. Whether Facebook can deliver on that grandiose vision before his ad revenue dries up will be his biggest challenge yet.

Network Defects

As Meta tries to reinvent itself, other social media platforms find themselves in a similar predicament, needing to keep engagement levels spiked in order to generate as many ad impressions as possible. Just as print media saw advertisers ditch them for the duopoly of Google and Facebook, the same may happen to the mainstream platforms, once audiences start to drift away to private, invitation-only social hubs, as Zuckerberg anticipates.

The mainstream platforms also happen to be highly susceptible to consumer fickleness, falling out of favour the moment people see their social circle flock to a new app, like jaded club-goers in search of a cooler vibe. TikTok is a perfect proof point of that sudden shift in wind direction, with GenZ now embracing the short-video platform as their search engine. They spend one third more time on TikTok than people do on either Facebook or Instagram7. “It has brought authenticity back to social media”, says one addicted user; another calls it “the heroin of social media”; “It really is our own YouTube and Google in one”, says another twenty-something user. These comments8 are typical of how youths view the platform: a place where “we’re able to be a community”. It is a social media platform that thrives on the imagination and cultural influence of a burgeoning creator class who make money shilling for brands.

Another platform on a hockey stick growth trajectory is BeReal, the photo sharing app that exploded in popularity last year with its novel approach to “in the moment” sharing. In contrast, the once buzzy audio chat platform Clubhouse is barely mentioned anymore. And does anyone remember Vine? Hyped as the next big thing — gone, in just four years. Plenty of other platforms (Google Plus, Meerkat, YikYak etc), whose value was never clearly apparent, quietly expired.

There is no doubt that social media is on the cusp of new era. The network defects now outweigh the network effects. Still, there are nearly five billion social media users worldwide. According to Pew Research 72 percent of U.S. adults have at least one social media account. They visit on average seven social media sites per day. In fact, in 2022, the average daily social media usage worldwide was two and a half hours per day (in Canada, it’s a couple of hours9). Social media has become the primary channel of communication for many people — the way they keep in touch with friends and family, share life events, and follow the news.

In China mobile-driven social media platforms like WeChat are a way of life. WeChat has been likened to a Swiss Army Knife — an all-in-one “super-app” — that represents the future of social for everyone: a multi-purpose, mobile-first platform that is a must-have accouterment to everyday life. Outside of China the race is on to become the next WeChat, used to shop, pay, chat, message, play, listen, stream, and engage, anytime, anywhere. TikTok is in that race — so is Apple with its closed ecosystem – so will Facebook be, once it finally figures things out, although by then it may just be a hangout for geriatrics.

The paradigm shift away from “town squares” to social hubs (or “digital campfires”10 as they have been called) is also picking up momentum, led by the gamers, who love to congregate on platforms like Fortnite and Twitch with their buddies, livestreaming their gameplay, while interacting with each other through text, voice or video. One of the more popular platforms is Discord, just eight years old but with 150 million monthly daily users already. In that short time it has evolved from a chat room developed initially for die-hard gamers into a community-hosting service for anyone who wants to create a private group. Users can find almost 22 thousand existing public communities dedicated to a wide range of topics, or set up their own gated group where they can message each other, share content and conduct video chats.

Mastodon is a decentralized platform which quickly became popular as an alternative to the “argumentative hellscape” of Twitter after the Elon Musk takeover. Users can set up a Mastodon server and host their own “Twitter-like” community. The advantage of this platform is that it operates on open-source protocol where independent servers can connect as if they were on a single unified platform like Facebook. The owner of each server is in charge of setting and enforcing the community standards and rules. Members can scroll through chronologically-ordered posts from their friends without an algorithm behind the scenes manipulating what they see — just the way social media was intended to work until the model was ruined by the commercial need to optimize engagement.

This growing trend toward the formation of niche communities will force brand marketers to cut back on increasingly ineffective social advertising (clickthrough rates are now less than 1%11) and swing their attention to social selling: using social media to not only make it easy for people to buy products, but spawning support communities designed to sustain brand relationships over time.

Already people expect to be able to reach out to brands through public platforms with their general inquiries and feedback. Take Coca-Cola, for example, with 109 million followers on Facebook. As you might expect, Coca Cola posts a lot of promotional content on its page, mainly contests and giveaways. But every post draws a smattering of complaints: a reference to PFSA chemicals in orange juice — a complaint about vending machines being empty — a protest against a Coca Cola dairy supplier accused of animal abuse. Even a goodwill post from Coca Cola announcing a major donation to Black Lives Matter came under fire: “I’m sure your tune will change once the bottom line takes a hit”.

Most companies, not just Coca Cola, are fumbling their real-time responses, either letting the complaints and service requests slip by unnoticed, deliberately ignoring them, or taking too long to respond. A more responsive and streamlined governance structure is needed to integrate all social media channels with customer service and marketing so that the internal handoffs can be smoothly managed.

The most promising opportunity for brands is to push the boundaries of social commerce as China is already doing. Social media is no longer being used as just another waypoint on the customer journey, trying to draw people into a conversion funnel via sponsored posts. Instead, it is becoming a one-stop-shop where a user can learn about a new product through “shoppable content” (say, a short-form video or photo), jump to a product detail page for more information and then go to a checkout page to buy that brand without exiting the platform. Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube now make it easy today for brands to showcase their product catalog, set up storefronts, and stage live streaming of promotional events.

A Feeling of Belonging

As social media becomes a primary shopping channel where people go to discover and buy products, brands will need to make it the linchpin of their go-to-market strategy. Social media will transition from being largely an awareness building channel to a more holistic relationship management ecosystem made up of both public and private networks. The various mainstream platforms will remain the preferred way to publicly showcase the brand, just because they reach so many people, but complementing that channel will be a galaxy of micro-communities, reserved for personally identifiable customers who are keen to develop more of an intimate connection.

Most brands today maintain a public presence on Facebook, Instagram and YouTube, with the more youth-oriented TikTok catching up fast as a popular choice to connect products with people. And as TikTok surges in popularity, thanks to its supremely tuned recommendation engine, older age cohorts are bound to follow. For now the most effective platforms for ad reach are the twin goliaths, Facebook and Instagram. After all, the stats are pretty compelling: there are two billion daily active users of Facebook — a massive potential audience, targetable by interests and behaviour — spending an average of thirty minutes a day on the platform. More than half of those users are followers of brands or are actively in market researching what to buy. Almost one fifth of them start their online shopping on Facebook. Although average engagement rates are less than 1 percent, Facebook accounts for 72 percent of web traffic referral12, making it a vital source of eCommerce leads.

Driving high levels of engagement on Facebook and Instagram is of course totally dependent on producing compelling content. The brands that have enjoyed the most success are lifestyle oriented products and services seeking to inspire their followers. GoPro represents a best-in-class example, earning 11 million followers by featuring one mesmerizing photo or video after another submitted by product users in response to various awards contests (e.g. “Photo of the Day”, “Anything Awesome Challenge”). Red Bull also makes extensive use of video in its posts, showing all types of wild stunts and extreme sports activities, completely aligned with its positioning as an adventurous and energetic brand. And of course the master of lifestyle storytelling is Nike with its 38 million followers on Facebook and another 150 million on Instagram, celebrating the achievements of sports stars while serving as a source of inspiration for the everyday athlete.

Yet even mighty Nike, famed for its marketing prowess, cannot shield itself from the trolls. When the company recently announced an innocuous update of its Facebook cover photo, featuring its legendary slogan “Just Do It”, the post woke up the anti-woke mob: “My wife and I will never buy Nike again. Good luck with your future virtue signalling”; “Don’t buy Nike. They’re more interested in politics than product”; “Go woke…go broke. You and the likes of you are ruining our once great country! Never again will I buy a Nike product!”.

A Facebook page is less like an orderly town square and more like a town hall filled with vocal supporters and critics. Pity the poor social media manager trying to pacify the crowd. Dealing with the “haters” can be traumatic. Which is why a safer haven for brands is to develop their own distinct communities where they can more easily control exchanges with customers, knowing they are made up mostly of fans who just want to feel like “insiders”. As the renowned marketing consultant Mark Schaefer says, “The last great marketing strategy is community”.

Much of what passes for community building today is merely an extension of the customer service function. Usually a support forum is created where customers can get answers from other members, usually as a cost saving measure to deflect inquiries away from the contact centre. But to cultivate a true feeling of belonging, brands need to go beyond support forums to harness the passions and shared interests of customers. The goal is to create a distinct social identity that will give customers a feeling of belonging to a special group. “You’re creating and reinforcing a set of beliefs, expressions and action for members to adopt and engage in”, advises community expert David Spinks in his book “The Business of Belonging”.

The customers with the strongest brand affinity — the “super-fans” — will jump at the chance to join, knowing they can hang out with like-minded members. They are eager to be involved, to have their say, to belong to something larger than themselves. And so they will be the first to participate in events — the first to share their experiences — the first to serve as “brand ambassadors” if anointed.

To grow organically, however, a community needs broader participation, and that’s where it gets tougher. Most members prefer to remain passive observers, content to periodically comment on other people’s posts. To get them to engage more frequently, a brand needs to incentivize them, offering recognition in the form of digital badges, rewards like free swag, or certain entitlements like exclusive access to events. The most active enthusiasts can be invited to join an advisory council for the opportunity to provide direct feedback and suggestions. And of course members are encouraged to share their personal stories with the brand by uploading content.

The work of community management can be immensely taxing and impossible to scale without adequate resources or tools. The community manager has to have a thick skin to moderate intense discussions, respond to barbed comments, banish disruptive members, and make sure people are behaving within the boundaries of acceptable conduct. The most gruelling job, however, is fuelling member enthusiasm and activating engagement. That can involve organizing discussion groups, staging meet-ups and events, and recruiting influencers to create content. “You’ll be like a hamster on a wheel”, says David Spinks, “constantly searching for ideas to keep your community engaged.”

A community management platform like Khoros, Circle or Discourse can alleviate the stress by streamlining the workflow and routing conversations to the right internal group while automatically recognizing and hiding improper content. And instead of renting space from Facebook Groups or Reddit to host the community, a fully owned community management system can be fully integrated with the brand’s web site or CRM systems, making the customer experience more seamless.

Community Matters

By now most marketers appreciate that social media is not merely just another ad-serving medium. Nor is it a customer service channel. It is a customer experience capability that needs to span the enterprise. Marketing might take the lead on content creation, on moderation, on social advertising and selling, but all other customer-facing areas of the business must learn to weave it into their operational routine. Because in today’s world people expect to communicate and interact through social media, not just with each other in private, but with the brands they care about the most.

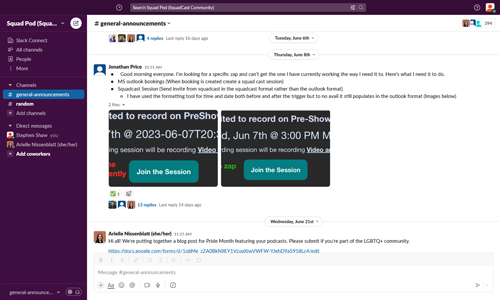

Figure 5 – Community management platforms like Slack make it easier to

manage daily conversations with members.

According to a recent survey by the National Research Group, 73 percent of U.S. adults consider themselves a “superfan” of at least one brand. They participate in brand communities; they submit online product reviews and ratings; they join discussion forums; they voluntarily form their own fan clubs; and they follow their favourite brands on Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Instagram. The most relevant conversations are happening across this constellation of networks and marketing’s job is to both listen and join in whenever it has something meaningful to contribute.

The path to becoming a social brand is not an overnight transformation. For one thing, the pressure of producing interesting but ephemeral content every day, while dancing to the relentless drumbeat of comments, can drain the resources of any marketing department. Today social media accounts for 23 percent of marketing spending13, a figure that is bound to grow significantly in the years ahead as all marketing becomes social first.

Another adjustment is just the asynchronous rhythm of social media management, a never ending cycle of monitoring and reacting to emerging trends and spikes in social sentiment, without the time to full digest its meaning and implications. Most organizations are simply not agile enough to cope with the extreme variability, or have mature policies and processes in place to maneuver through the potential hazards such as legal landmines and privacy potholes. And then there is the measurement challenge. It is virtually impossible to justify the commitment in resources without pleading for a leap of faith from executive management. Crowing about views and likes won’t change many minds in the C-suite.

The development of an enterprise-wide social media capability requires an elevation in status from a strictly a front-line function to a core strategic competency that can directly improve brand health. It also means putting customers at the centre of the planning framework. Today social media operates downstream from marketing strategy and planning, viewed primarily as a distribution channel as opposed to being an intrinsic part of the customer experience. But with social media now taking up as much as one third of people’s time online14, the main goal of marketing should be to find ways of increasing social equity amongst brand enthusiasts.

A social brand humanizes all interactions with customers, treating them as stakeholders of the business. Its governing ethos: the community matters above all else. The strategic emphasis is on relationship building over time through authentic conversations: Help people find solutions to their needs through aided discovery; extend the experience to wrap the brand around their lives; invite them to become an active member of the brand community; and give them all of the post-sale support possible to overcome any issues they might experience.

For most organizations this approach is a radical departure from past marketing practice where people are merely numbers on a spreadsheet. Social media brings those numbers to life: not what, when, where and why people buy, but how they feel, what and who they care about, and what they love to do. The sole mission of a social brand is to become an integral part of people’s inner circle — to act like a confident, someone they can turn to for help, someone they can rely upon — forming a strong trusting relationship.

The unfortunate story of social media since its inception has been one of weaponizing words and sowing distrust. This next era will see it begin to emerge as a way for brands to restore trust and build communal spirit. Instead of trying to beat the algorithms and compete for views, marketers will simply try to create a shared sense of community where people can be a better version of themselves.

- “What resilience means to Nextdoor CEO Sarah Friar”, McKinsey & Company, March 2022

- According to Pew Research, 23% of adults in the United States in 2020 said they get their news from social media “often”.

- Max Fisher, “The Chaos Machine”, Little Brown and Co., 2022, Pg.25

- 2023 Social Media Industry Benchmark Report, Rival IQ

- “Elephants in the Room”, Scott Galloway, Medium, Nov.04, 2022

- “A Privacy-Focused Vision for Social Networking”, Mark Zuckerberg, Facebook/Notes, March 2019

- “Average Time Spent per Day by US Adult Users on Select Social Media Platforms 2022”, eMarketer, April 2022

- “Lawmakers Want to Ban TikTok. Here’s What Users Say Is at Stake”, New York Times, May 7, 2023

- “160+ Social Media Statistics Marketers Need in 2023”, Hootsuite, January 2023

- “The Era of Antisocial Social Media”, Harvard Business Review, Sara Wilson, February 2020

- “85+ Important Social Media Advertising Statistics to Know”, Hootsuite, April 2023

- “42 Facebook Statistics Marketers Need to Know in 2023”, Hootsuite, January 2023

- “CMOs: Adapt Your Social Media Strategy for a Post-Pandemic World”, Harvard Business Review, January 2021

- Social Media Trends 2023, Hootsuite

Stephen Shaw is the Chief Strategy Officer of Kenna, a marketing solutions provider specializing in delivering a more unified customer experience. Stephen can be reached via e-mail at sshaw@kenna.ca